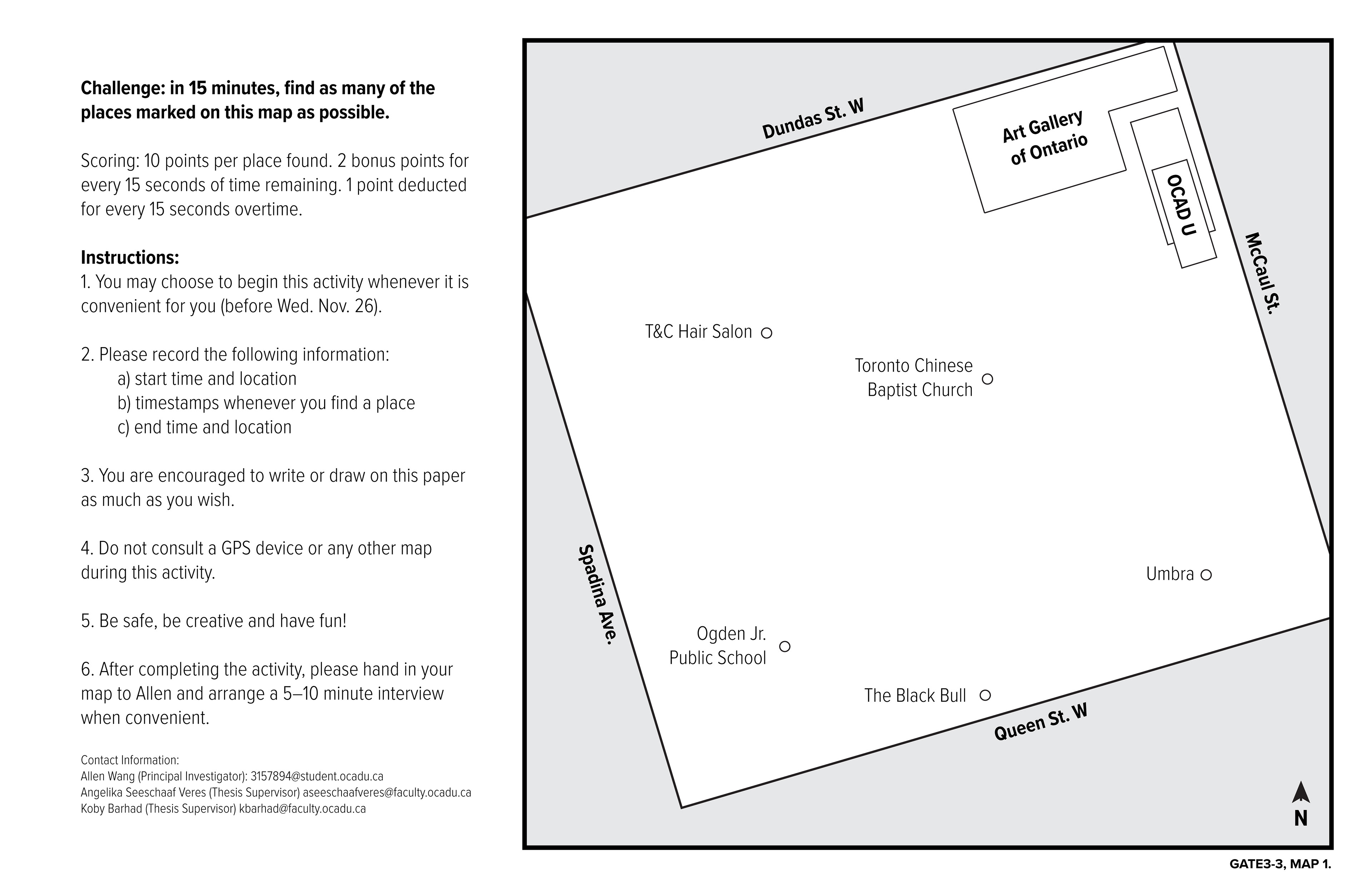

“In fifteen minutes, find as many of the places on this map as possible. You may not use other maps or GPS devices to assist you.”

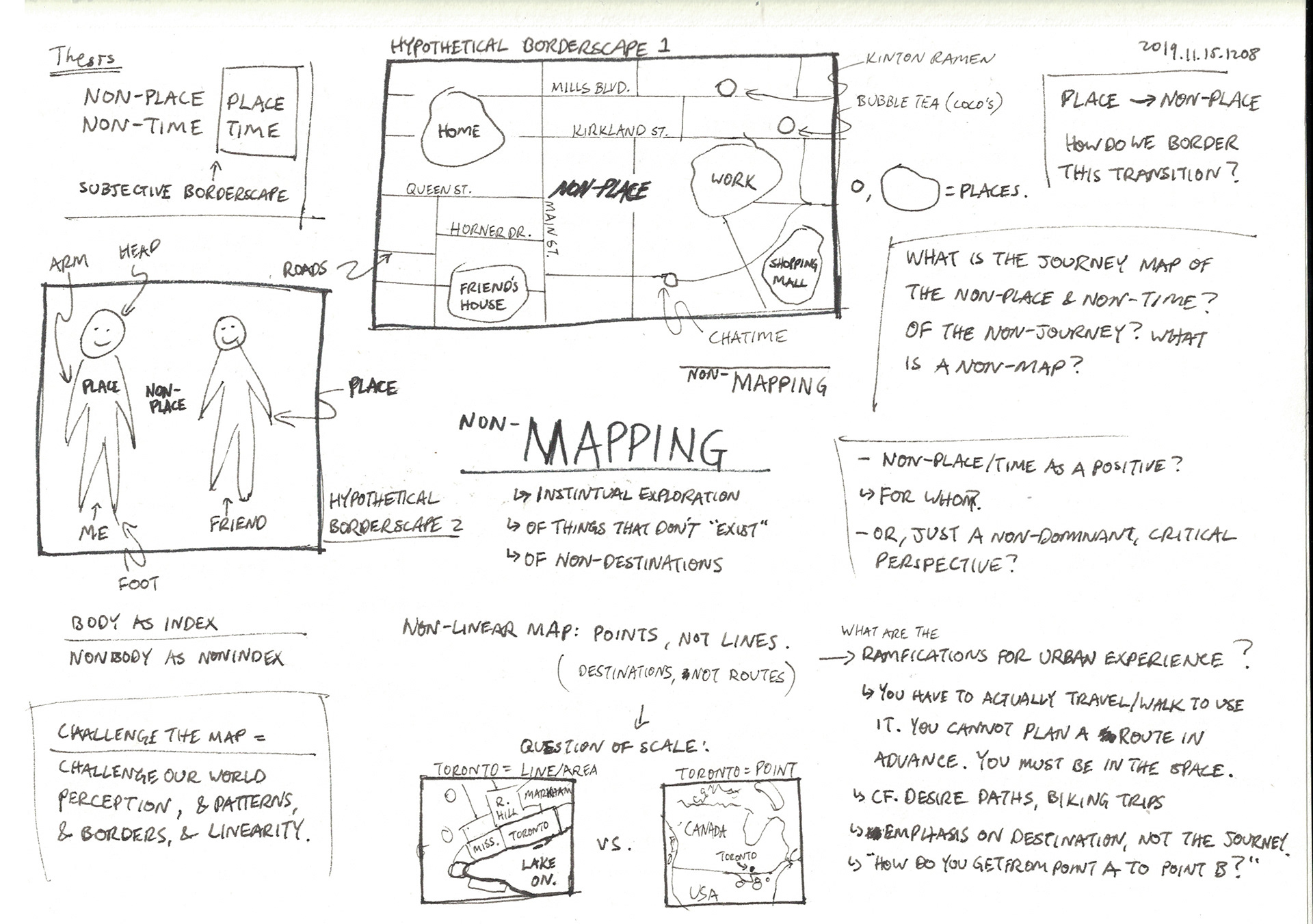

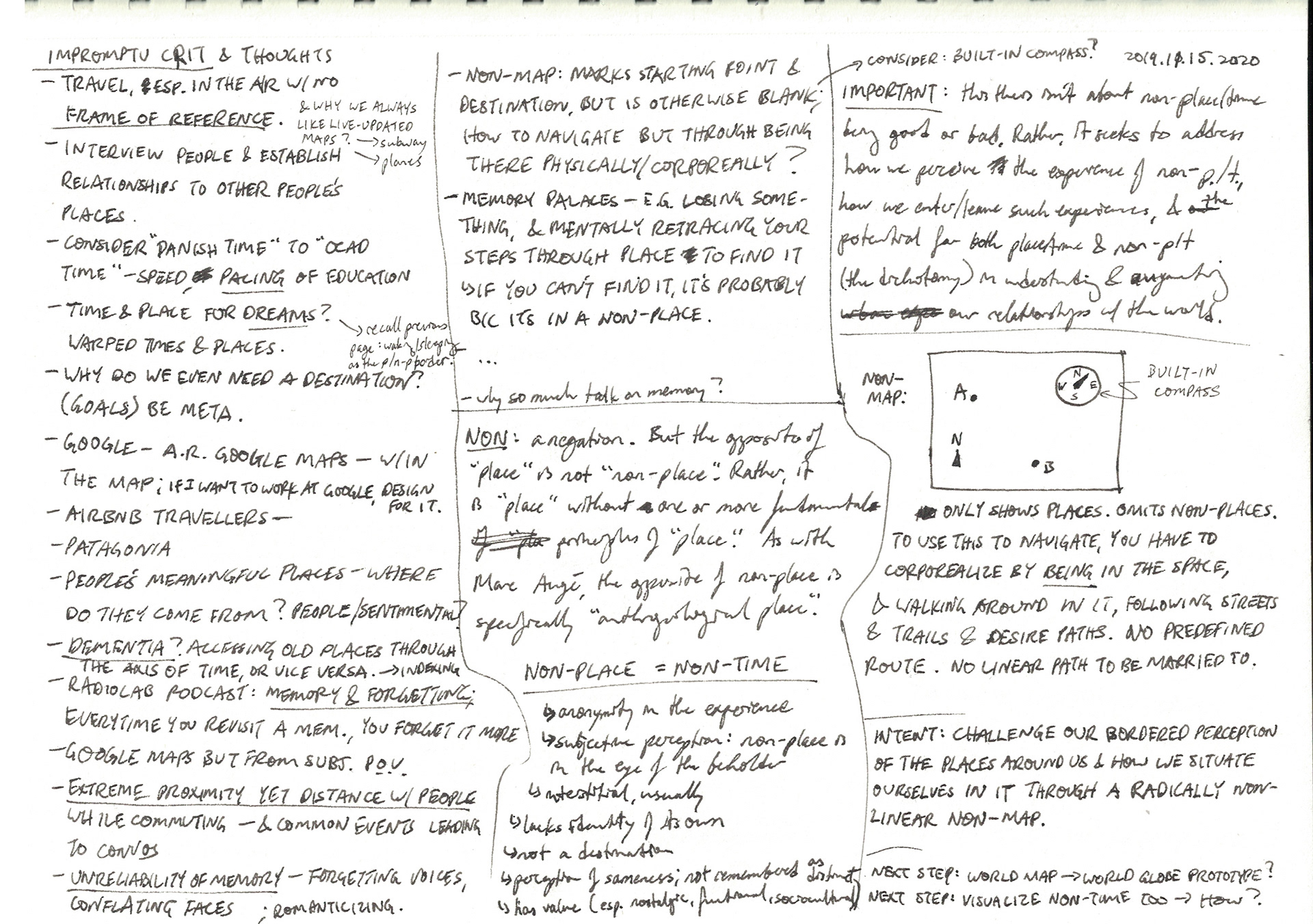

How do people feel when they engage with the experience of being in a non-place (i.e. being between places, or lost)? What tactics do they use to navigate in them?

(I recommend you first read the Non-Linear Mapping project, which provides pertinent background context and a theoretical framing for this investigation.)

ACTIVITY

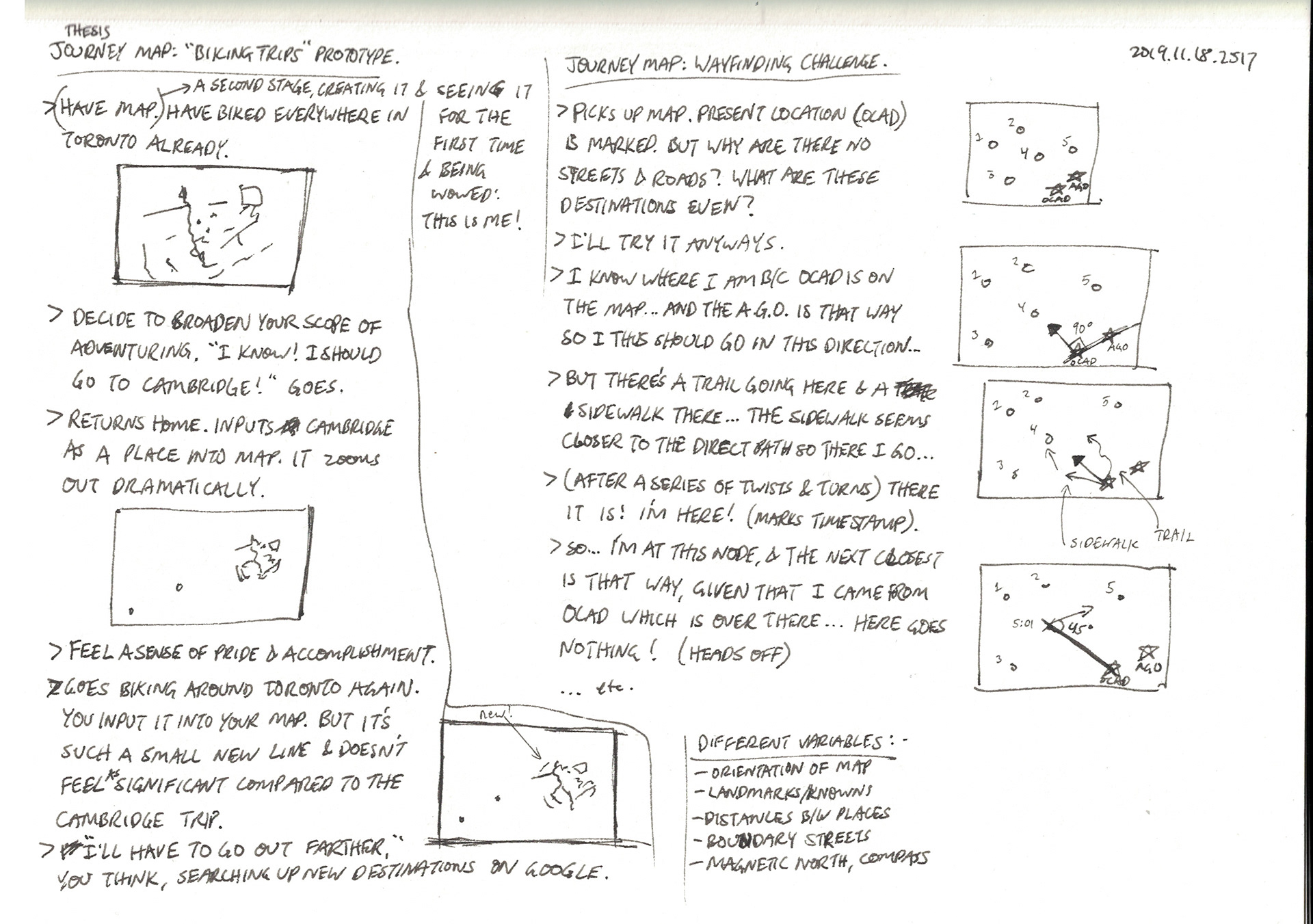

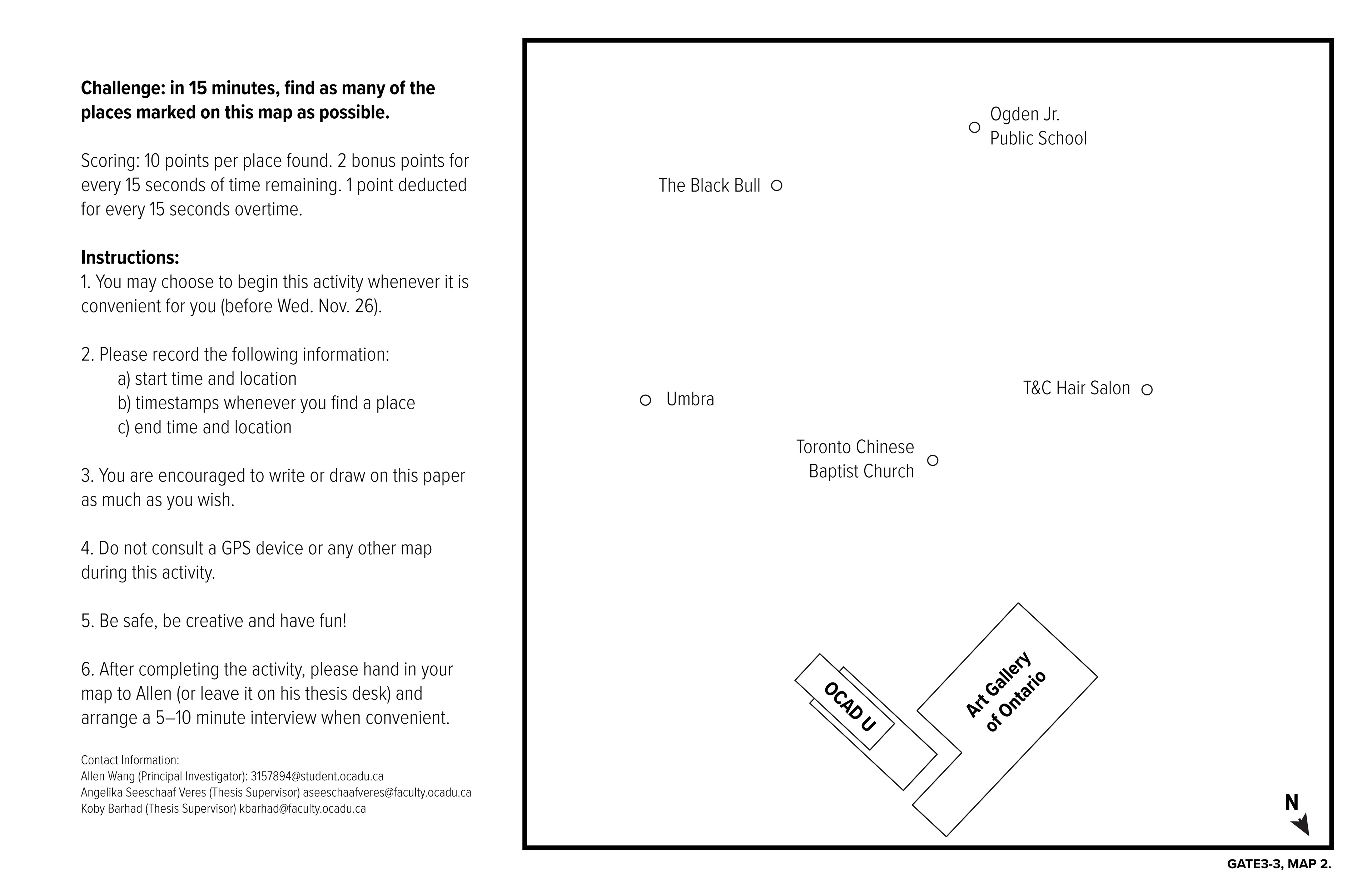

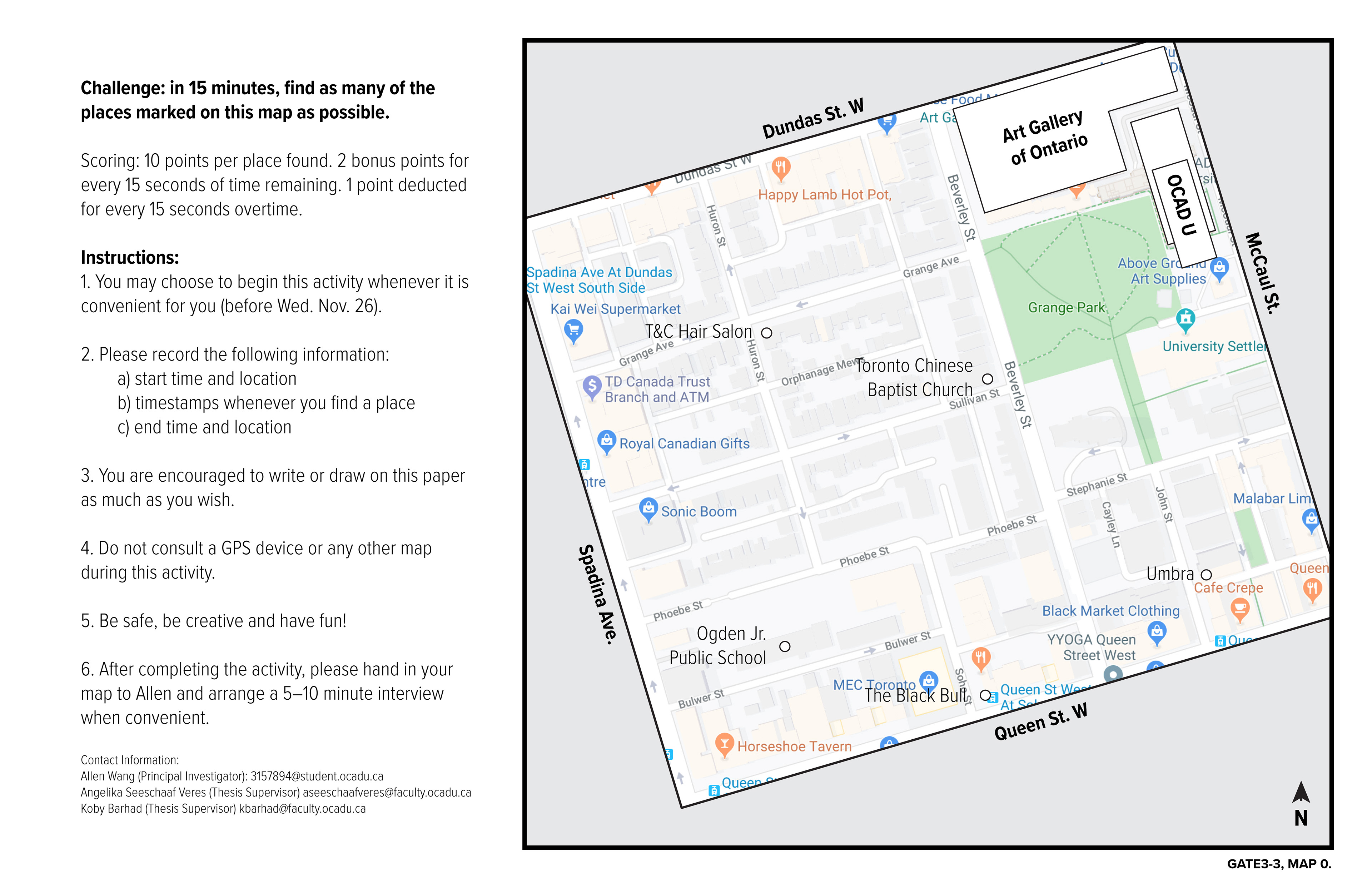

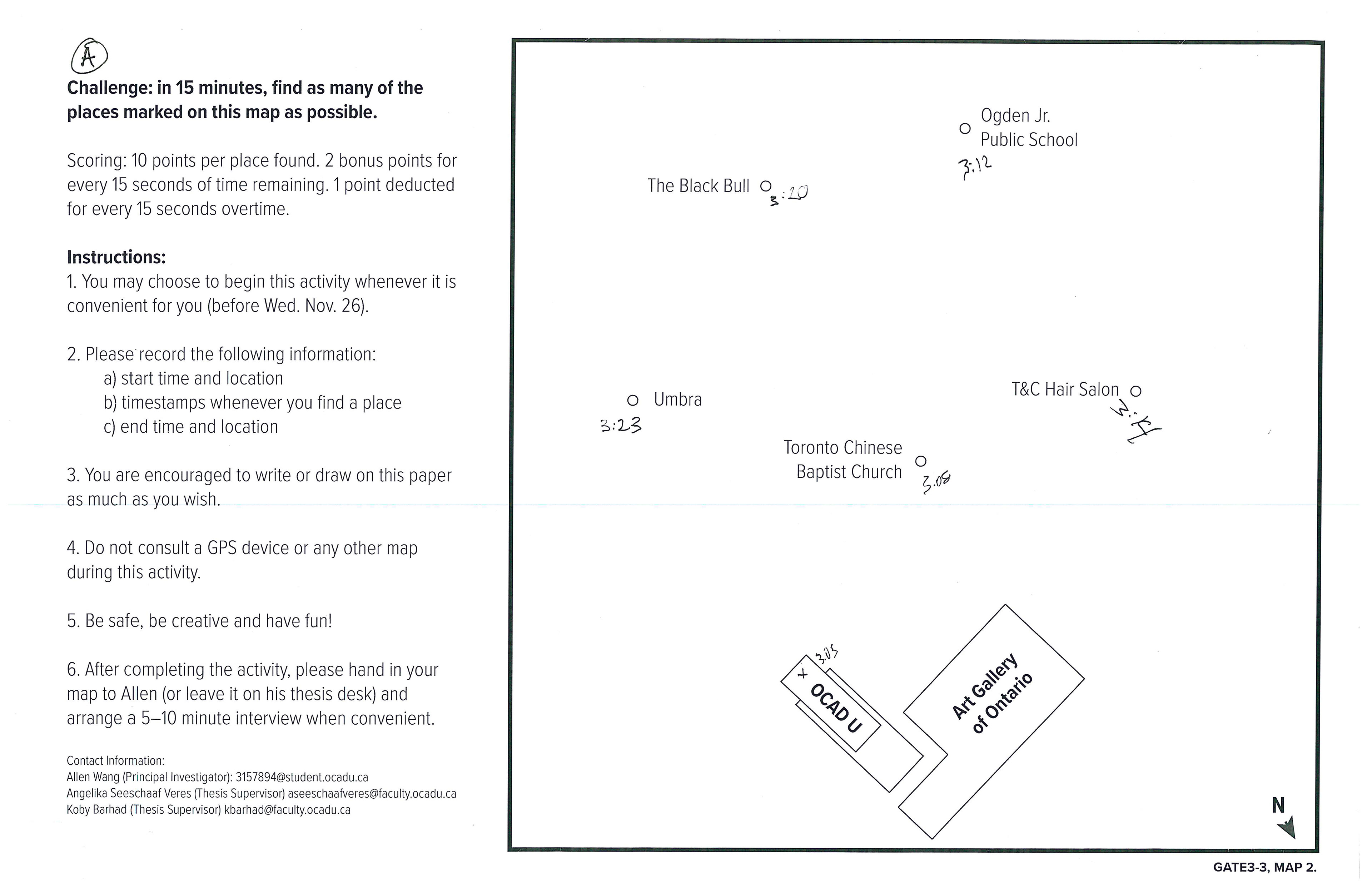

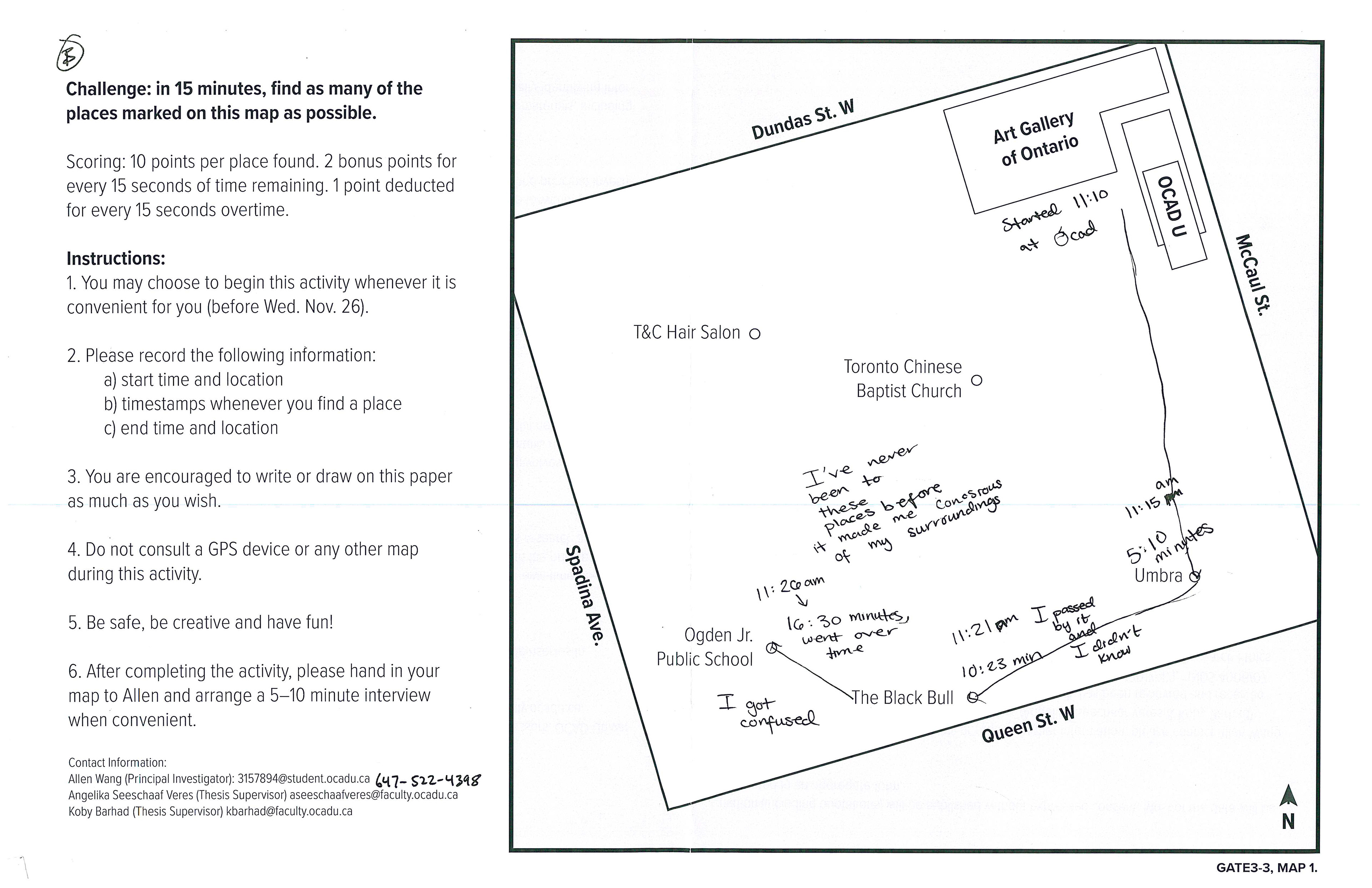

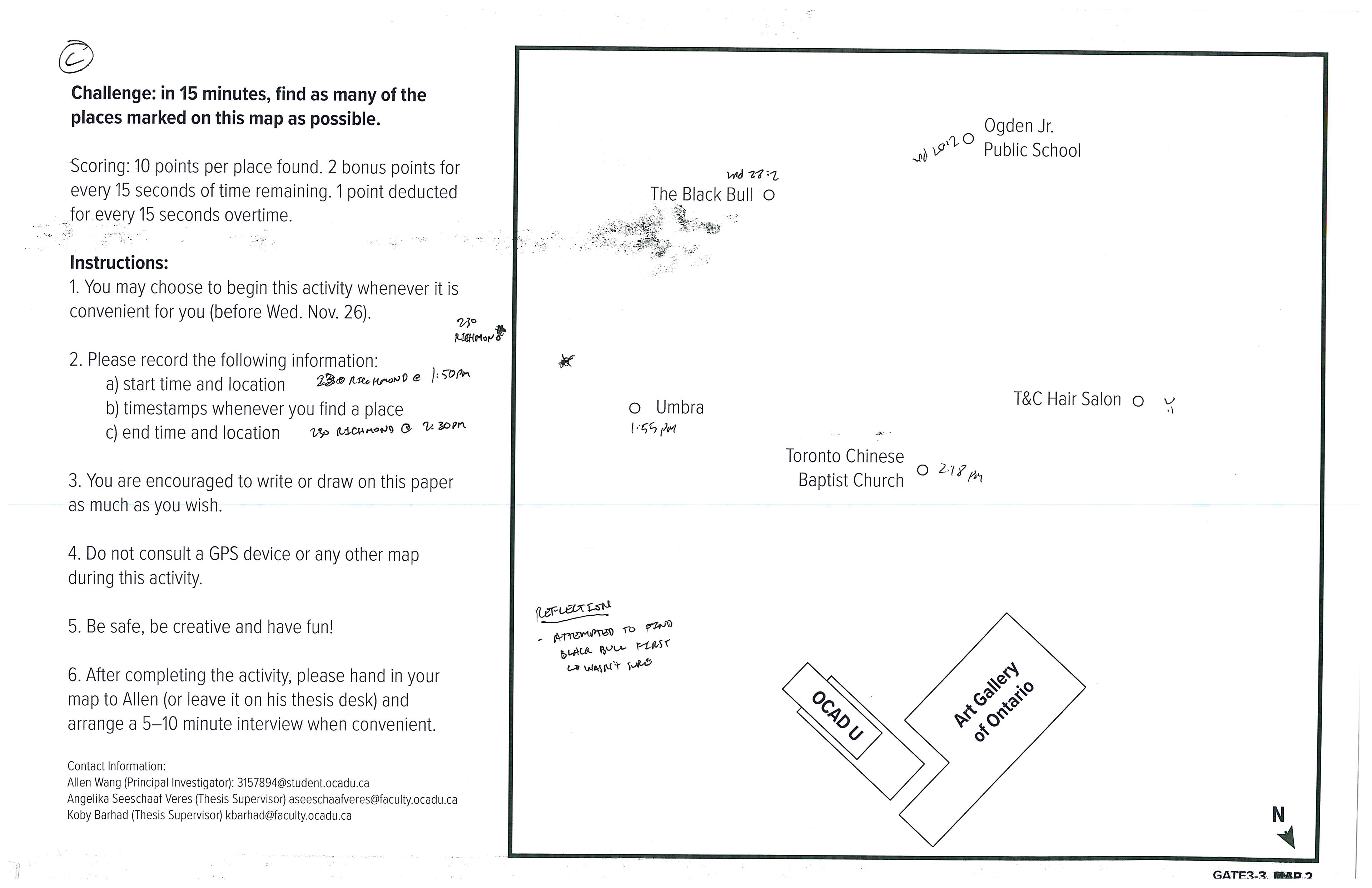

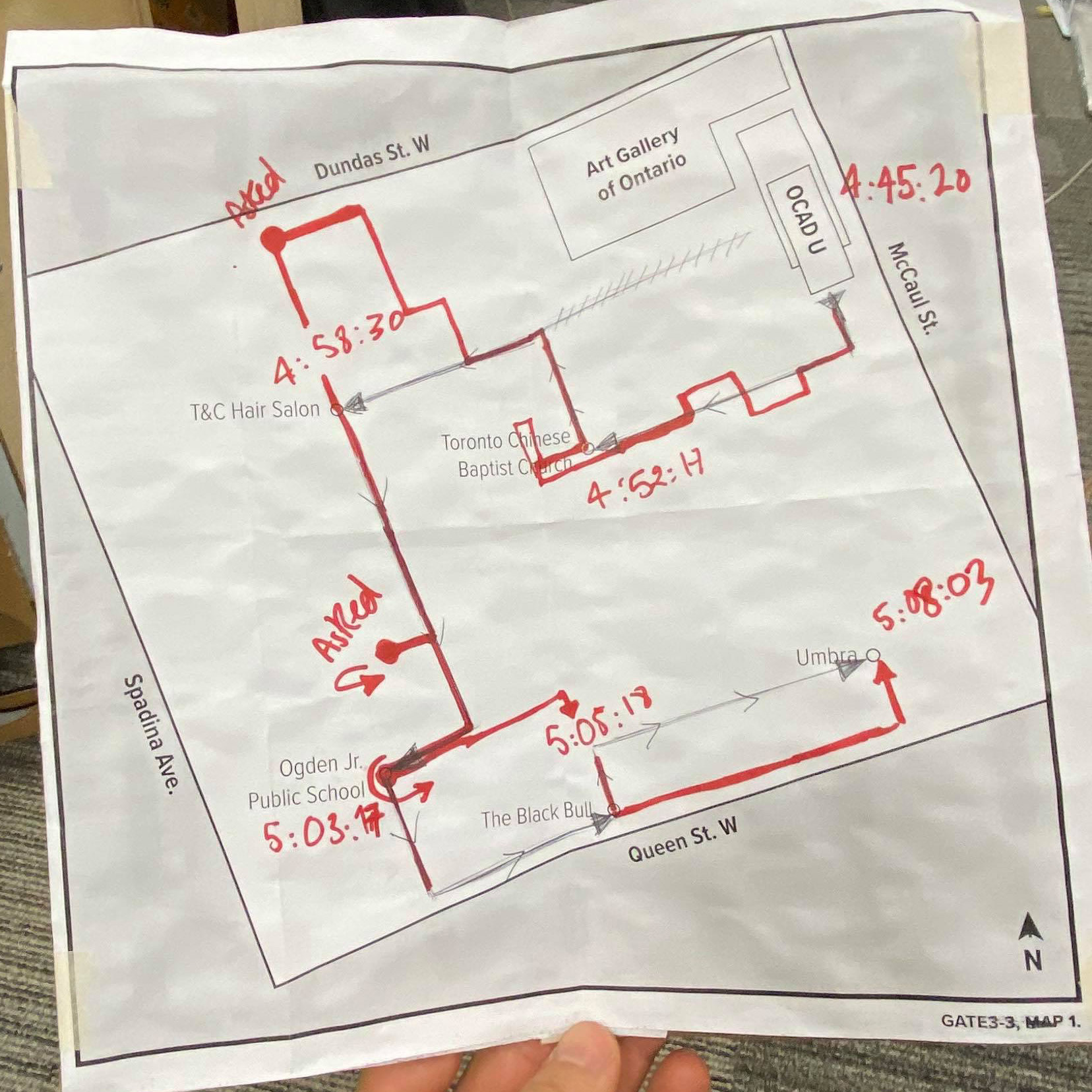

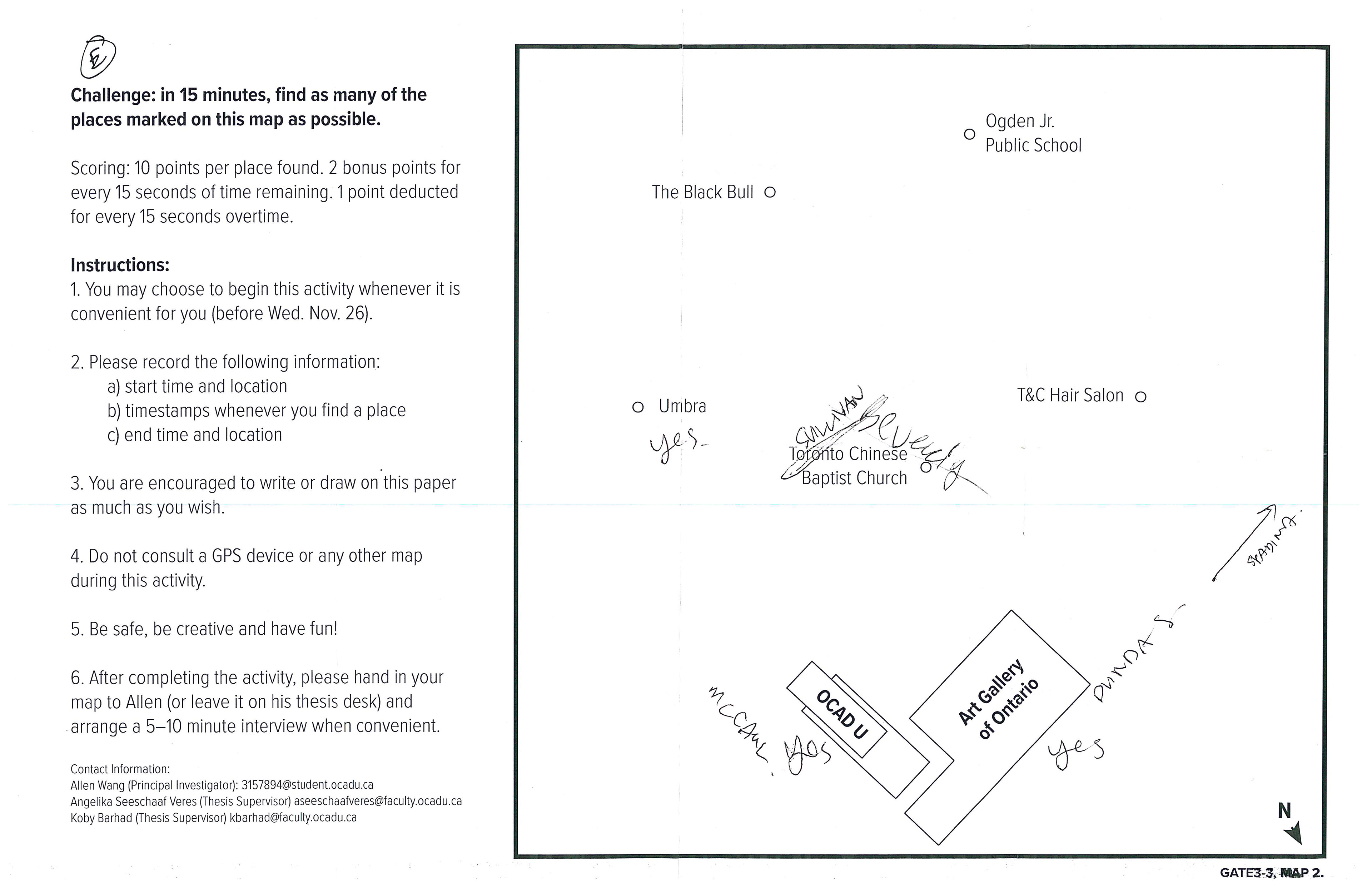

In this research activity, I explored self-situating and wayfinding tactics in a gamified format. I provided each participant with one of two maps featuring the same five destinations, but with different frames of reference: an “easier” map with more generous information, and a “harder” map which was more cryptic. I asked them to take fifteen minutes, on their own time, to find as many of those destinations as possible without consulting another map or GPS device. I encouraged them to annotate or otherwise modify the maps to their advantage. To add a competitive edge, I scored participants on the number of places found and total time spent on the search. Afterwards, I conducted semi-structured interviews with the participants to debrief and discuss their overall experience of the activity and their thinking processes.

PLANNING

I engaged thirteen participants, mostly from the pool of current OCAD Industrial Design thesis students. I approached prospective participants in person and handed them one of the two maps (printed on tabloid paper), which also contained the instructions and consent form. Ultimately, six people participated, of which three (“B,” “D,” and “F”) had the “easier” map and three (“A,” “C,” and “E”) had the “harder.”

Location: Selected because it was in close proximity to campus (from where I expected most participants to foray), had a healthy balance of “known” and “unknown” destinations for the participants, and being residential, would also be safer to wander in.

Time: I intended the fifteen-minute format to strike a balance between depth and convenience; short enough to be an enjoyable detour or a break, but long enough to provide meaningful, personal investment into one’s actions—and some time to think.

Map Iterations: From home with Google Maps and Street View, I created eight morphological variations on the same map. After testing one in person, I revised them into a set of two: “easier” and “harder,” and also updated a few of the locations.

DEBRIEFING

I asked each participant to arrange a 5–15 minute semi-structured interview with me following completion of the activity. At this meeting, they walked me through their experience and handed in their annotated maps. The interview had five main questions:

1. Describe your level of familiarity with the neighbourhood, and with orienteering skills, before the activity.

2. Please run me through your overall route and plan. What strategies did you use to help you find your way? How well did they or did they not work?

3. What was your emotional experience throughout the activity? How did it change between starting out, finding the first location, and at the end? Or, how did it feel to wander around in the white spaces (non-place) on the map—to know/not know the way?

4. How did the time constraint and/or scoring system impact your experience and decision-making?

5. If you/I were to run this activity again, is there anything you/I would/should do differently?

PARTICIPANT FEEDBACK

As Participants D & E expressed, fifteen minutes was a very short amount of time for the activity, in which finding all five destinations would be nigh-impossible. Participant B suggested it would be nice to include walking times between destinations. Participant E found the challenge very difficult, but also questioned the viability of making it easier—which could potentially “take the fun out of it.”