Abstract

Mountains hold a lot more than just rock and snow. They carry stories about people and their changing relationships with the environment.

Since the 1950s, Nepal’s ecotourism industry has grown rapidly, turning the Himalayas into sources of income and national pride. But today, the increasingly visible effects of climate change, pollution, and natural disasters are destabilizing how people who work in tourism—like guides, porters, lodge owners, storekeepers, and local communities—think about the future. Many are leaving the mountains (if not the country) altogether, raising serious questions about how sustainable this way of life really is.

This project argues that caring for the environment means more than just managing waste. It calls for a deeper shift: from rethinking ecotourism as a form of environmental extraction to a form of environmental advocacy.

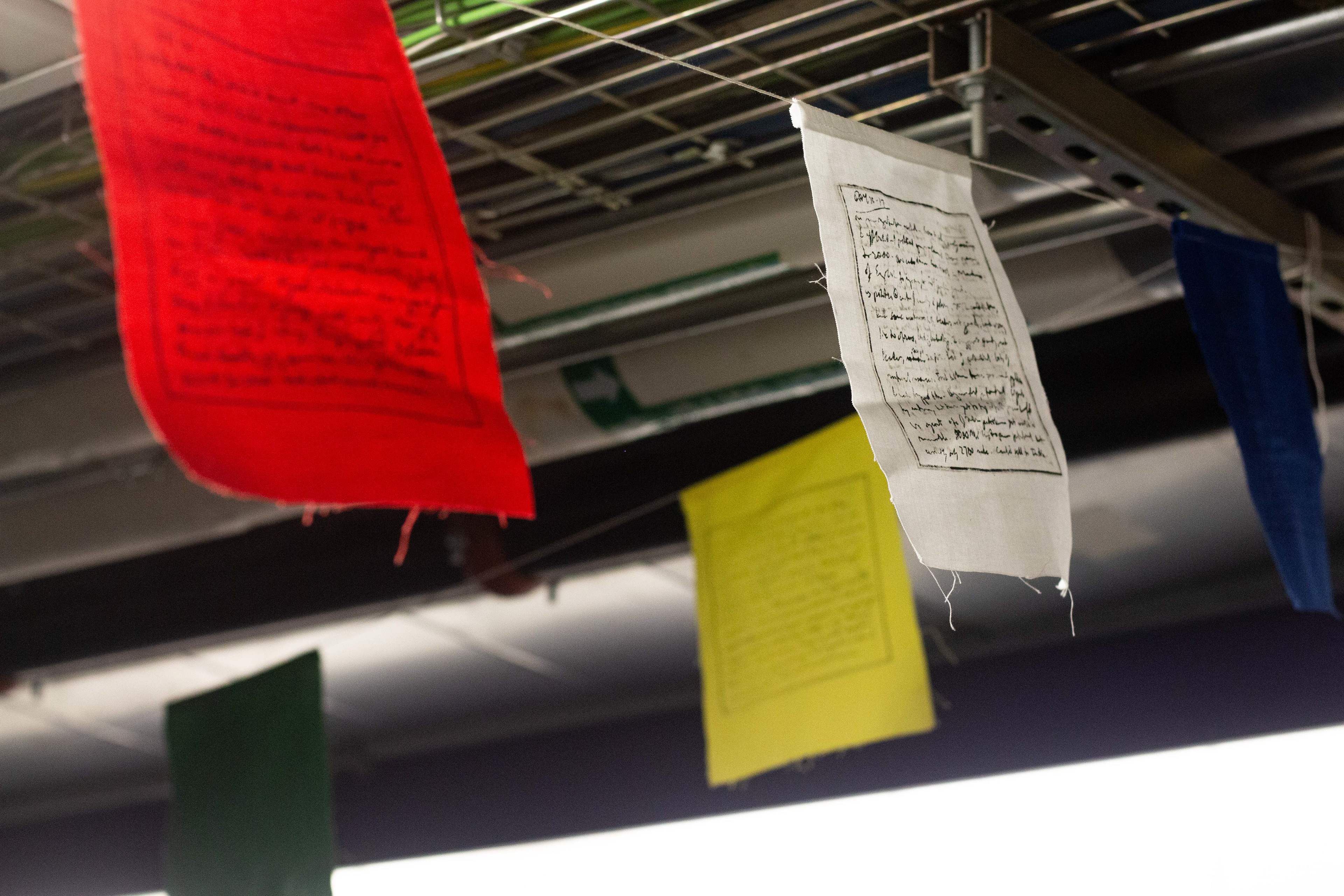

To help people around the world connect with what’s happening in the Himalayas, this project embeds data from my 2024 fieldwork (comprising photos, videos, field notes, and interview recordings) into familiar, everyday objects that tell a story. These “time capsules” include a deck of playing cards, a set of prayer flags, and a series of paperback books. They are designed to be sold in stores, to be shared with friends, to fill in the downtime while trekking, to be preserved as souvenirs, and most of all, to spark conversation about the changing mountain environment.

“A much more encompassing vision of climate change is needed, one that respects the ancient and powerful role that climate has played in the way that human society views itself and its role in the cosmos. Our analysis offers new insight, thus, into linking geophysical change at large scales and cultural change at small ones, linking the global and the personal. It suggests a need to see climate change as not something ‘out there’, or entirely out there, but as something also close and personal, something ‘in here’. It suggests the need to see climate as part of human ecology, including moral ecology. It offers an avenue toward understanding the outrage when belief in the climatic foundations of one’s community is challenged. The moral dimension explains the fervor of the denial; but it also points toward a powerful point of leverage, one that we did not even know existed.”

Dove, Michael R., and Daniel M. Kammen. “Differences in Perceptions of Climate Change Between and Within Nations: Studying science, scientists, and folk.” In Science, Society and the Environment: Applying anthropology and physics to sustainability. Routledge 2015, 116–117.

Part One: Thinking

Part Two: Making

Part Three: Sharing