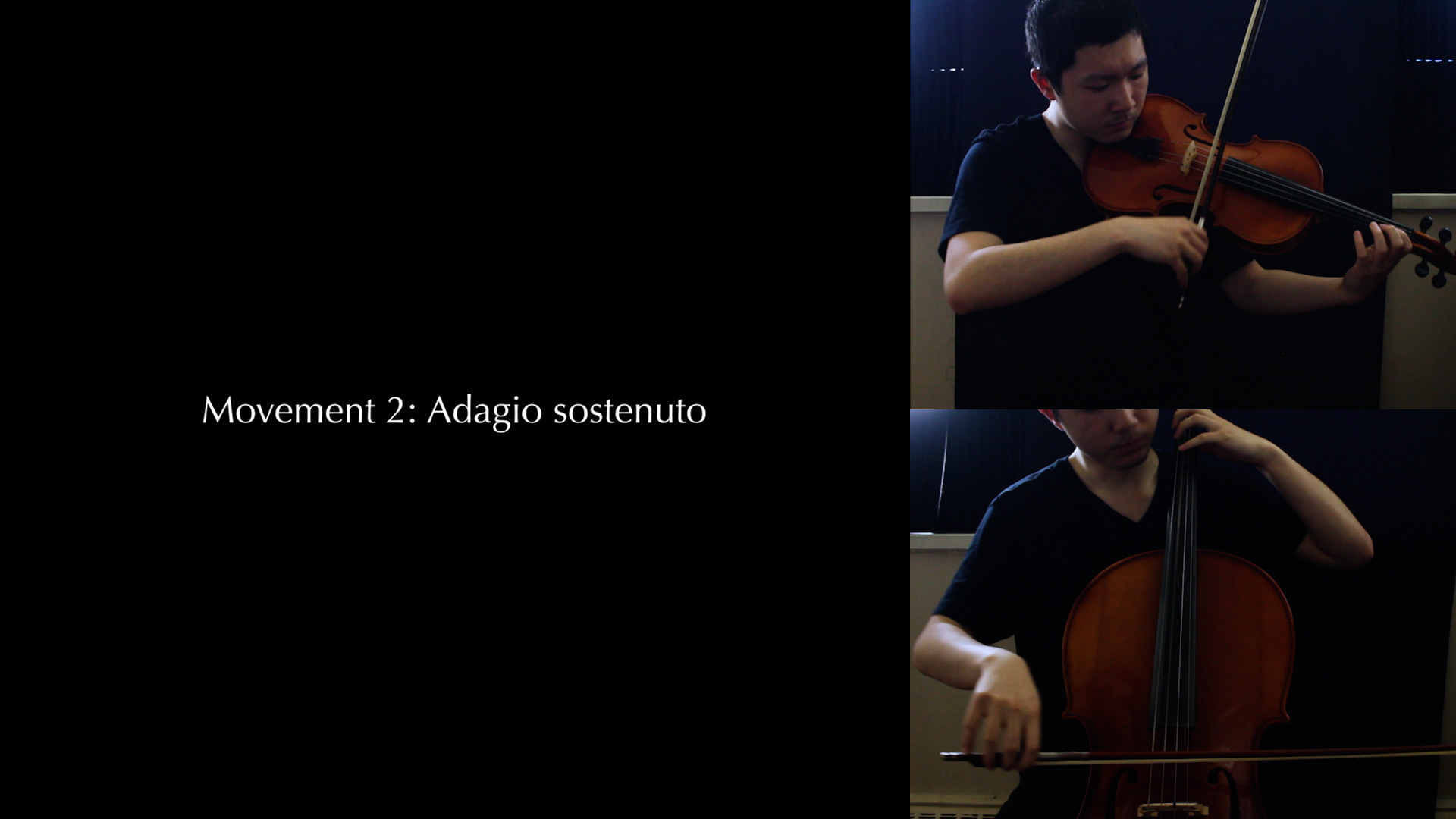

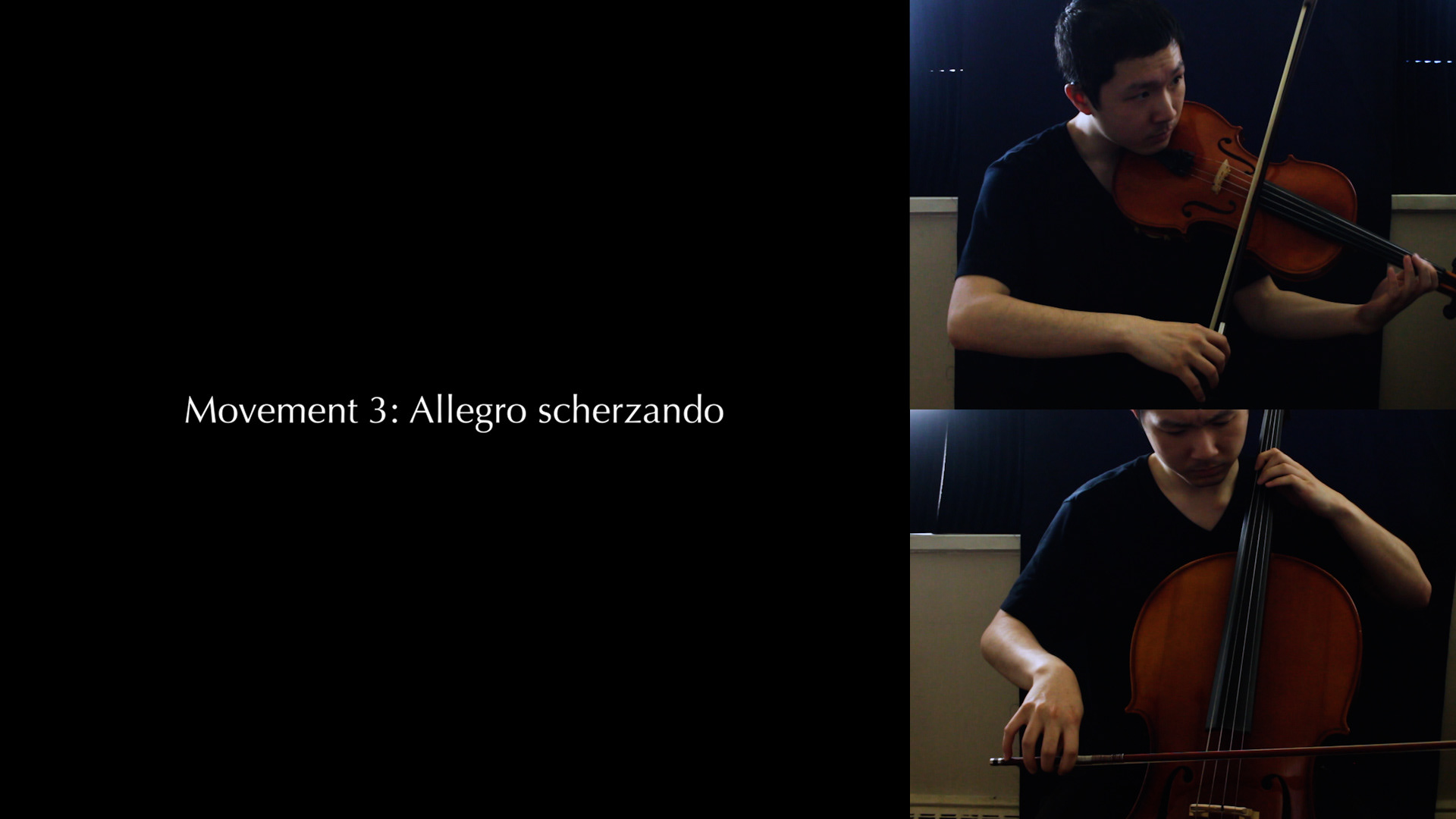

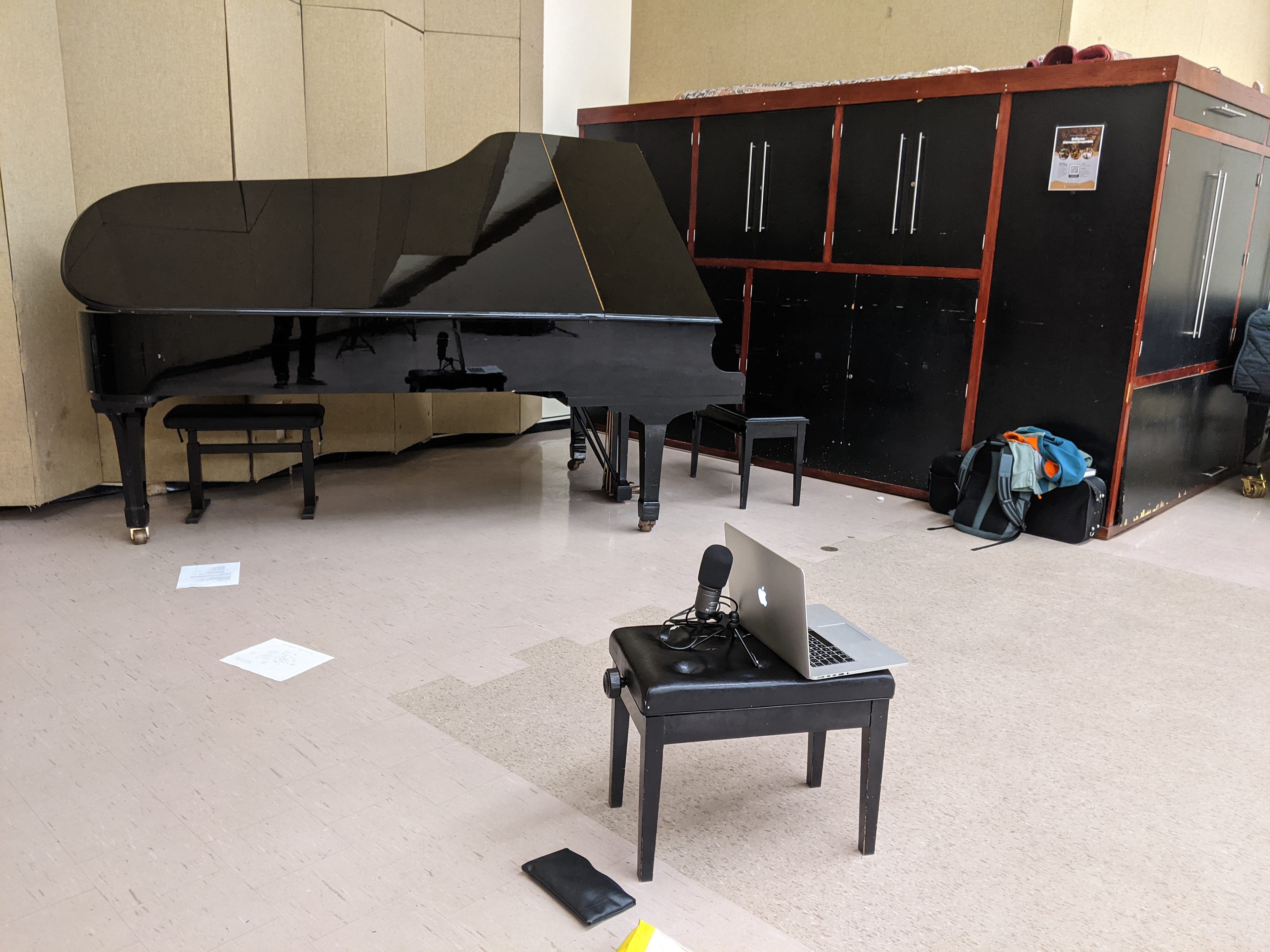

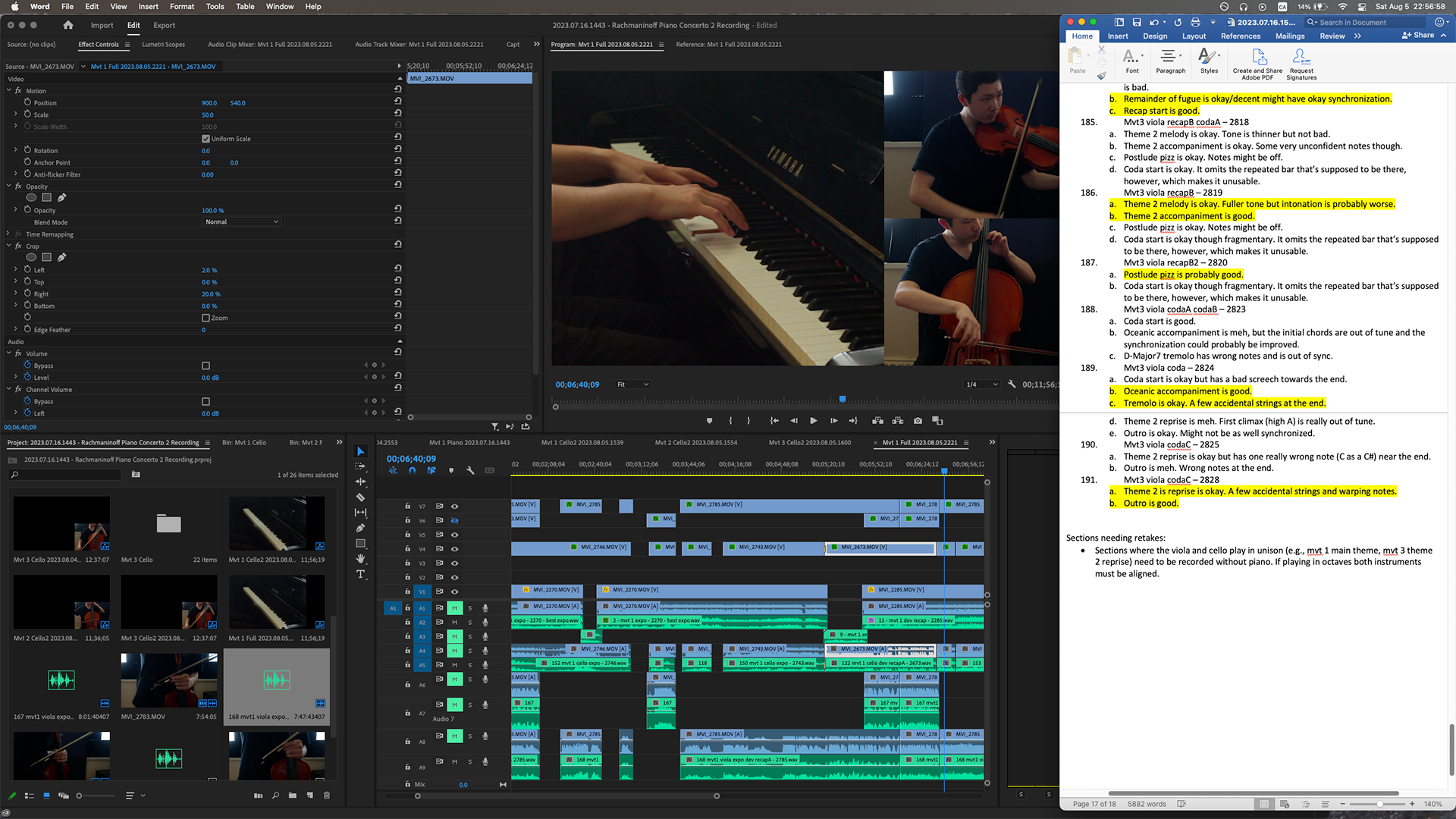

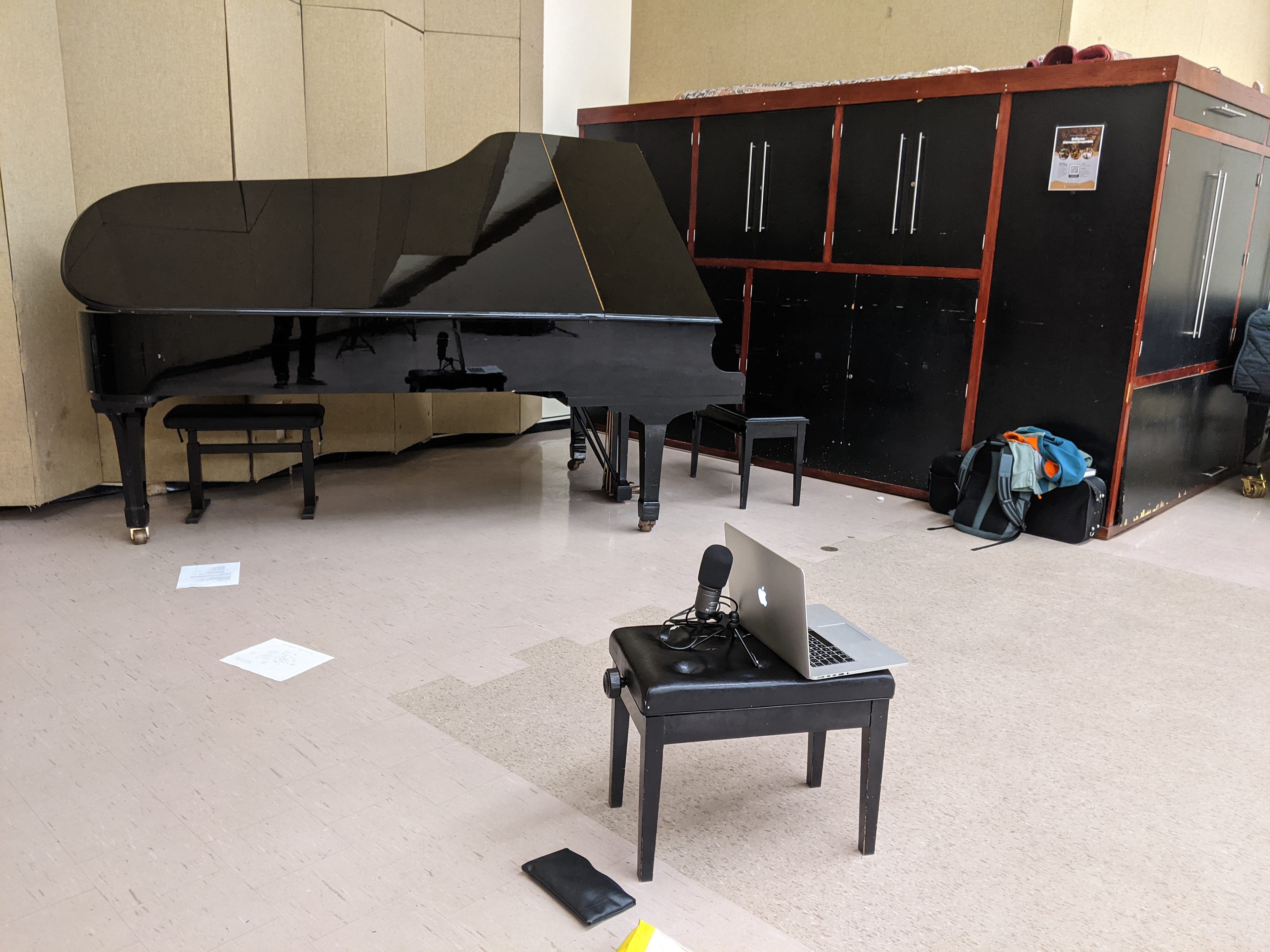

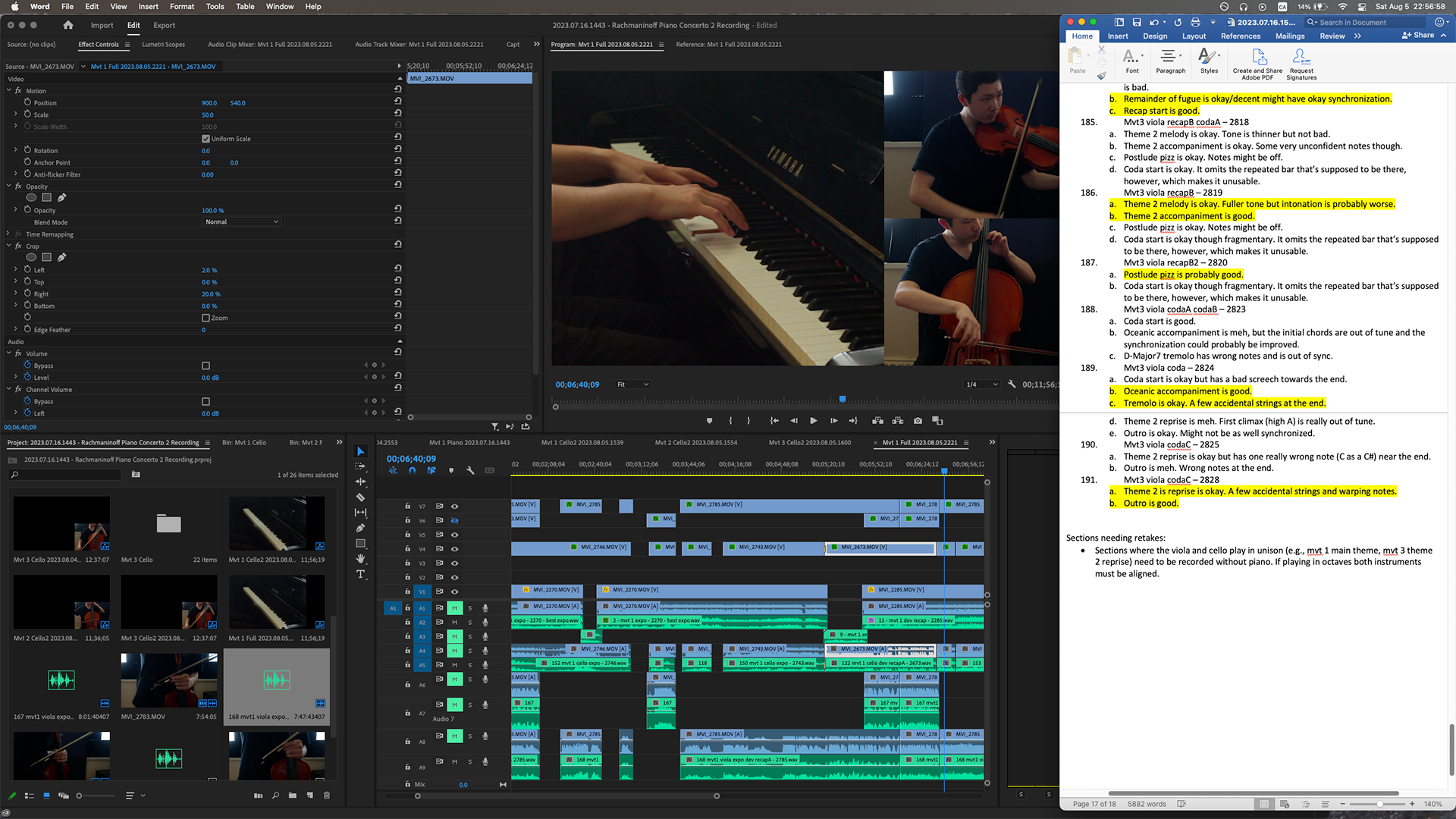

I first heard Sergei Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor in autumn 2019; I was playing in the viola section of the University of Toronto Campus Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Lorenzo Guggenheim, and the soloist was Alexander Panizza. A few months into the COVID-19 pandemic, I decided to take it upon myself to learn the piano part as something of a longer-term project, and worked on it on-and-off for two years. In late 2022, I had the idea to bring in my other two instruments (viola and cello) into the equation and cap off the project through a video wherein I would accompany myself playing the concerto in full. After some preparation and experimentation in different venues, I recorded the piano part at home across three weekends in July 2023, then recorded the cello part while listening to the piano part, then recorded the viola part while listening to the piano and cello parts together. By early August, I had recorded 232 discrete chunks of audio/video (mainly 1–6-minute takes of specific sections), of which 68 made their way somewhere into the final cut.