Remember Pokémon Go? It was a hugely-popular augmented-reality implementation of the Pokémon franchise for smartphones, released in the summer of 2016 by the San Francisco-based developer Niantic Inc. After peaking at 45M daily users worldwide and dominating social media, its playerbase dropped sharply but has actually stabilized and is still going strong today.

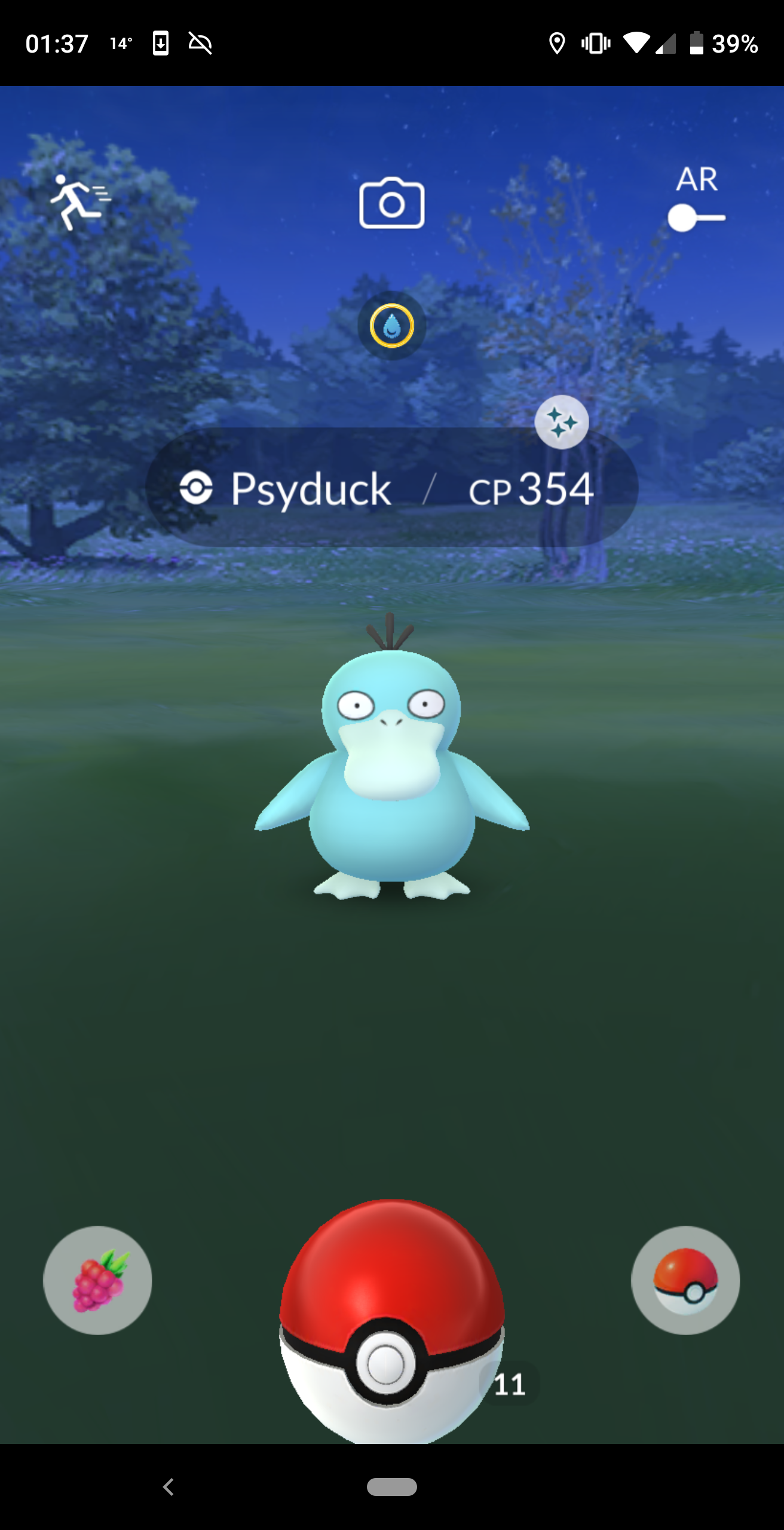

The core experience revolves around three gameplay loops: exploring, collecting, and battling. You play the role of a Pokémon trainer. As you walk around, you see Pokémon spawn around you, and you can throw Pokéballs to catch them. To acquire Pokéballs (and other gameplay items), you have to “spin” PokéStops which are situated at points-of-interest in your neighbourhood, such as murals, landmarks, and signs. Every trainer joins one of three factions and battles for control of “gyms” (i.e. special PokéStops) using the Pokémon in their collection. Throughout the day, “raids” may occur at gyms where you can team up with nearby trainers to battle a rare Pokémon for the chance to catch it. Gotta catch 'em all!

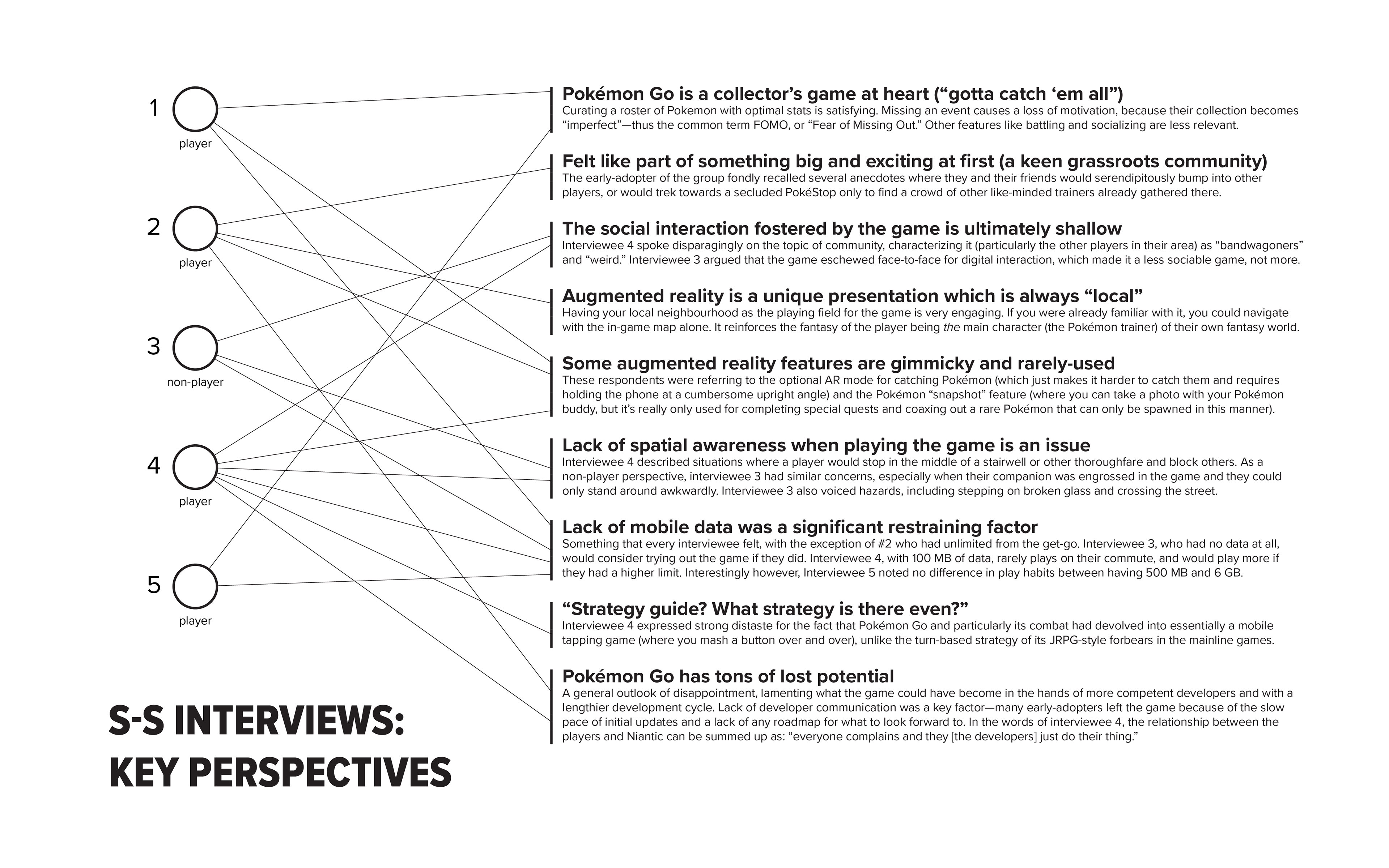

SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEWS

I began my research by interviewing four players and one non-player. After drafting up a list of research questions, I conducted three of these interviews in person, one through VOIP, and one through Facebook Messenger; they were 20–50 minutes in duration.

Though I found a wealth of suggestions for improving the game, what stood out to me most was the fondness that some players had as they recollected stories through rose-tinted goggles in the dog days of summer. Yet they also expressed apathy and even cynicism about what it had become. It was clear that perspectives on the game would be complex and multifaceted, but it was also clear to me that I really, really wanted to hear more people talk authentically about their experiences.

RAID ETHNOGRAPHY

Throughout September, I participated in twelve raid events at six gyms downtown and two gyms in North York. They were well-attended, Mewtwo and Giratina being popular raids, with 10–60 trainers present at each. I was particularly struck by how much the physical environment of the location impacted player behaviour and comfort (e.g., stairs to sit on, walls/pillars to lean against, overhangs for shade), and also thought about how weird it must have been for passers-by to watch a congregation of people materialize seemingly out of nowhere.

ONLINE SURVEY

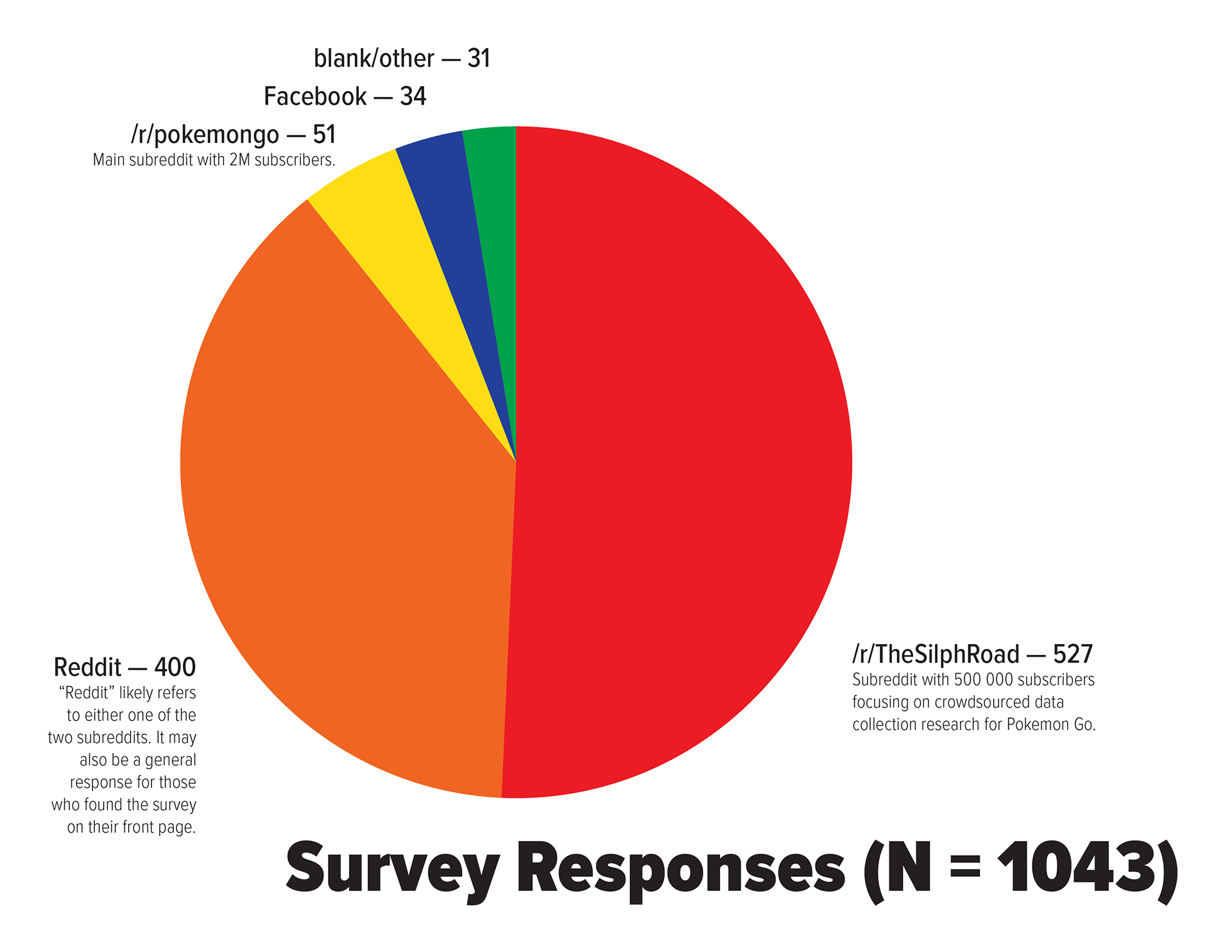

After reviewing past attempts by researchers at conducting surveys on subreddits related to Pokémon Go for cues on how to maximize outreach, I launched my own survey with six open-ended questions.

RESEARCH ETHICS CONSIDERATIONS

Following principles of research ethics outlined in TCPS 2, I ensured all participants remained anonymous, provided informed consent, and had the right to withdraw without penalty. The survey homepage explained the purpose of my research and provided contact information for both myself (the Principal Investigator) and my thesis professors. I did not ask participants to provide demographic or other personal information because I was solely interested in qualitative data. In curating what responses to reproduce in this portfolio, I avoided sensitive or overtly private responses, and heeded any specific requests for non-disclosure or retractions I received.

SURVEY OUTCOMES & FEEDBACK

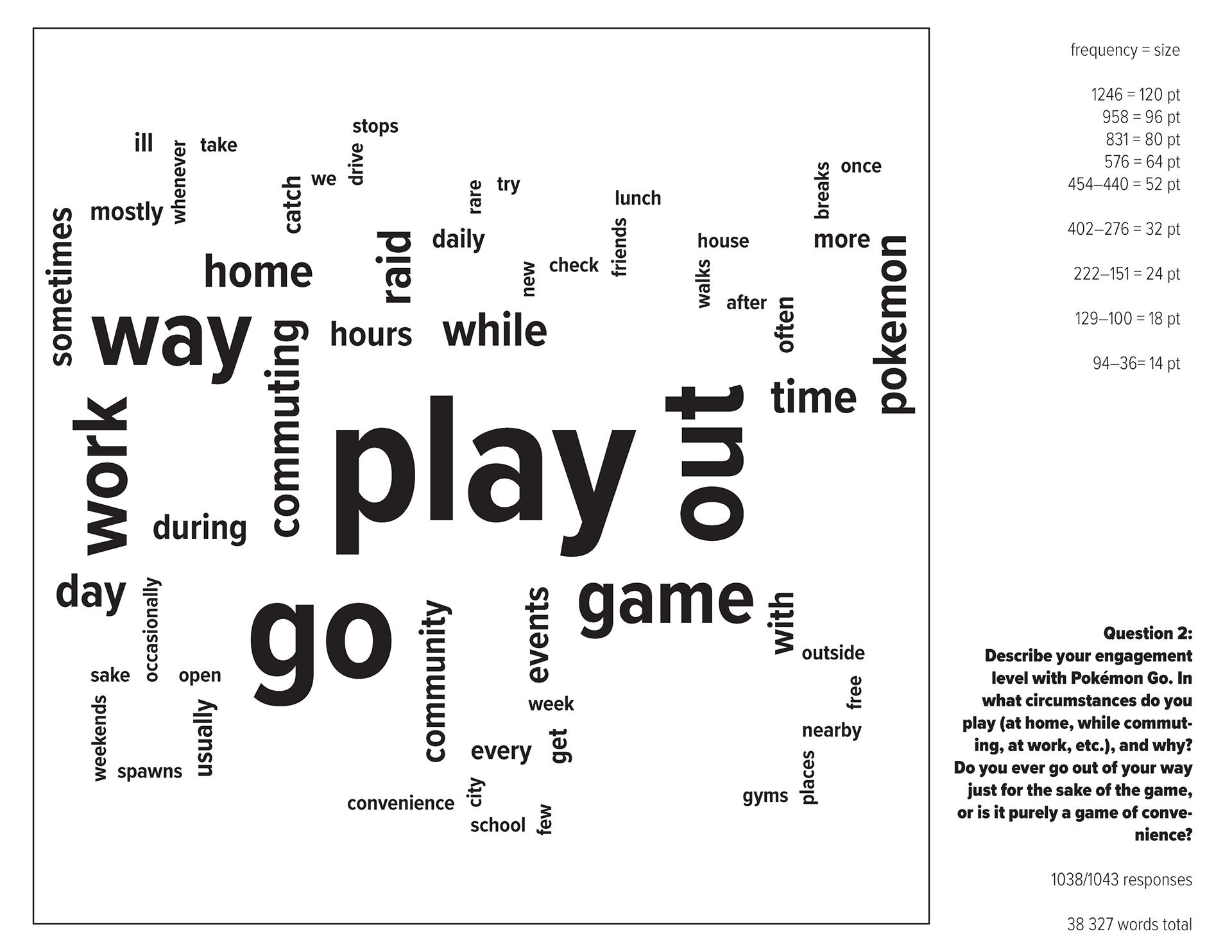

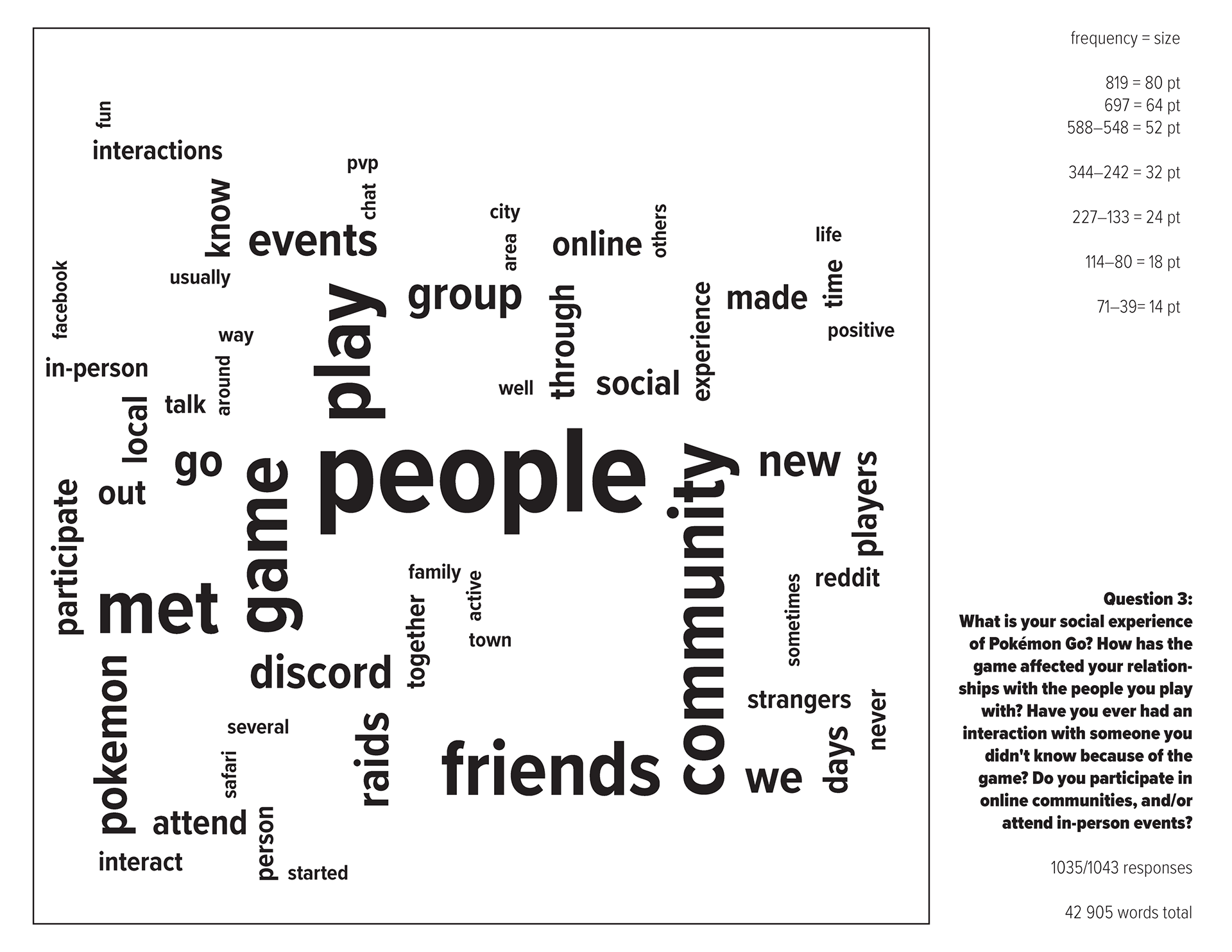

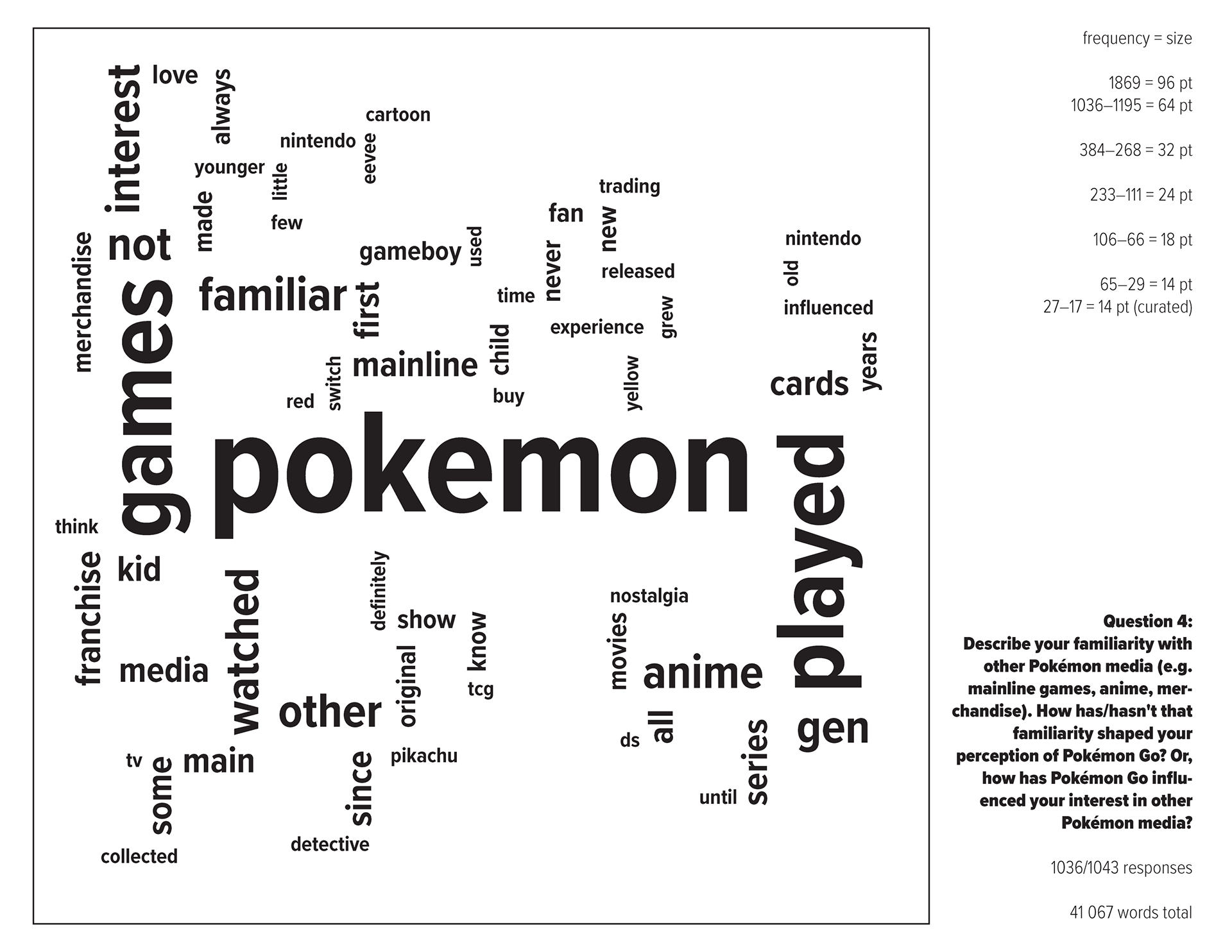

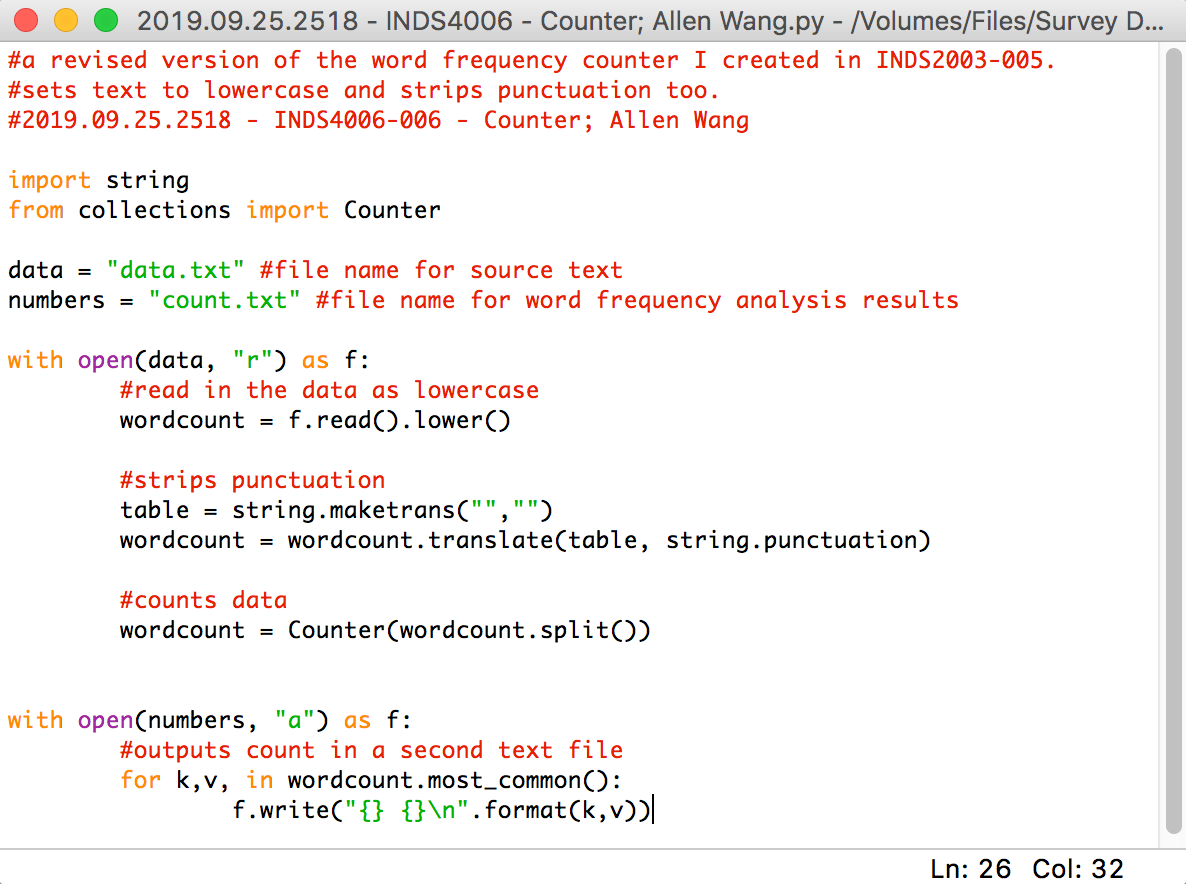

Over the course of 33 hours, I received a flabbergasting 1043 responses totalling over four novels’ worth of text (~220K words). With limited time to process this deluge of qualitative data (much of it passionately-written), I ran a word-frequency analysis through Python, then skimmed the text to pick out salient responses and keywords relevant to my emerging research interests.

One common feedback I received was that my questions were wordy and imprecise. Some questions were actually several in one (esp. Q1), which was confusing and difficult to code. In addition, I’d inadvertently prejudiced the open-ended responses by listing examples of things to mention (Q4 & Q5)—which meant they were over-represented in the analysis. I had intentionally avoided collecting any quantitative data (e.g. demographics, Likert scales, multiple/ranked choice), but due to sheer volume, this was a missed opportunity. A question I wish I’d asked was a simple “Describe Pokémon Go in five words” prompt.

DATA ANALYSIS

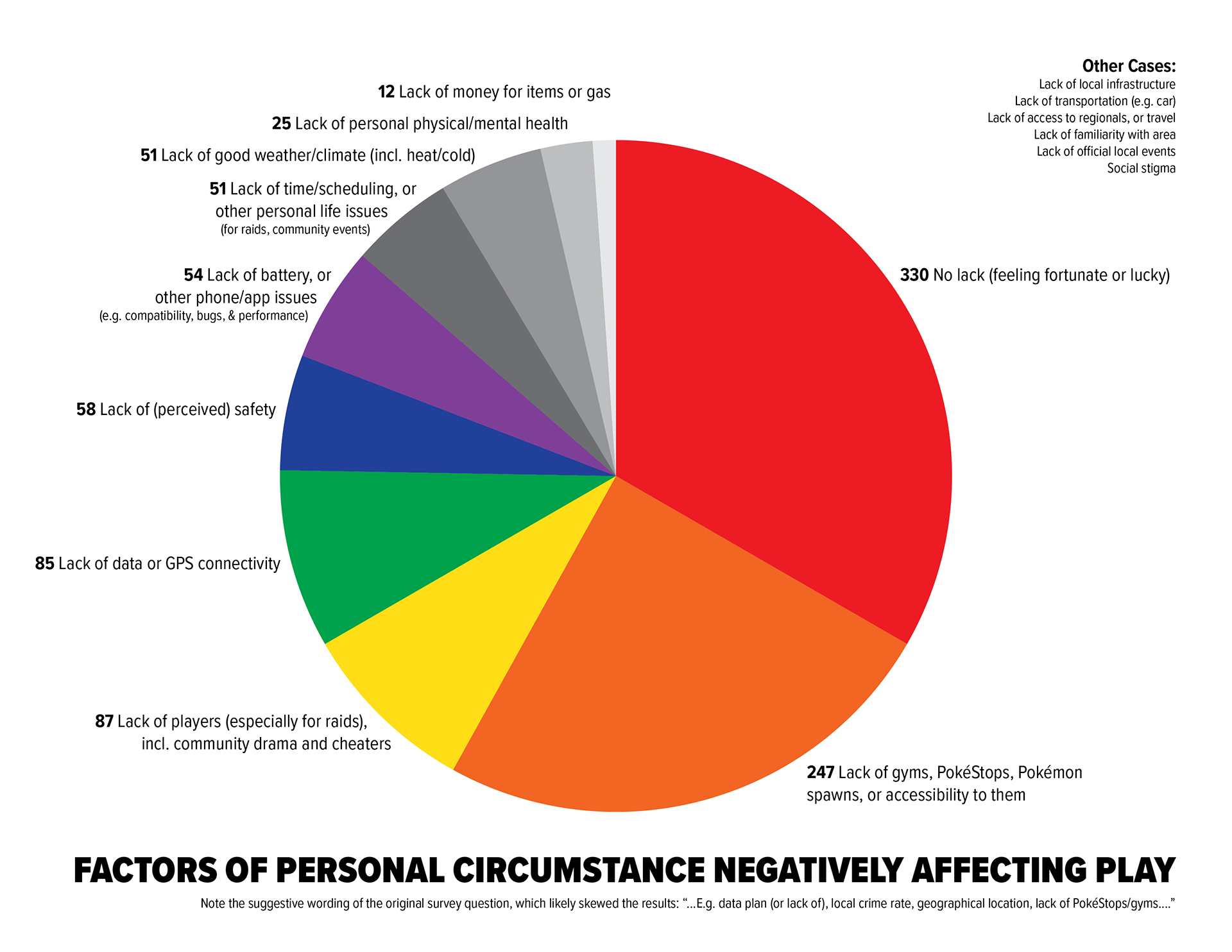

The topic I found particularly compelling was that of personal circumstances and how they affected one’s game experience (Q5). While approximately a third of respondents considered themselves in more-or-less ideal circumstances (often dense cities or campuses), I manually counted 670 mentions of deficiencies (“lacks”) that people experienced. Since I had been lurking on those subreddits for several months at the time, it did not surprise me that the lack of nearby PokéStops was the most common issue.

Another interesting topic was how trainers began to self-identify with reference to those in-game circumstances. Many described themselves as “privileged” or “lucky” to live in areas conducive to playing Pokémon Go. Some took pride in having contributed positively to the experience of other players in their local community—for instance, several players took up Ingress (Niantic’s previous A.R. mobile game) or submitted data to Open Street Maps to add more PokéStops to their neighbourhoods (something you could not do directly in Pokémon Go). On the other hand, there were also respondents who felt embittered by local Ingress players who, for various reasons, did not render this “service” to the “community.”

RESEARCH SYNTHESIS

INFORMATION AGE COLONIALISM

My research pointed towards an “Information Age Colonialism” through which the San Francisco-based Niantic exerted a dominant perspective on players around the world through its inadequate and closed curation of local PokéStops. Consequently, players felt frustrated and disenfranchised because they could not improve their experiences (make the game “easier”) despite playing a game taking place in their very own backyards. In the most pervasive example, rural players had to travel much further than urbanites to “spin” the same number of PokéStops and thus accumulate the same quantity of PokéBalls, and could rarely gather sufficient players to tackle the highest-level raids—leading to a sense of urban envy.

INTERDISCIPLINARY ANALYSIS: MYTH

Roland Barthes, in Mythologies (1957), described “myth” as a second-order semiotic system fusing the first-order “sign” with the invocation of cultural values (in plainer terms: just as words communicate meanings, fables instill morals). Myth is the mechanism where a specific and timely event becomes attached to a seemingly universal and eternal narrative (e.g. a soldier saluting a flag evokes patriotism, putting on a wedding ring symbolizes marriage). It accomplishes this through the dissemination of “normalized ideology” among the “undifferentiated masses,” often in the form of media and pop culture.

The Pokémon myth has a particularly compelling linguistic dimension—players of all backgrounds are equalized as “trainers,” who “battle” (not “fight”). Pokémon don’t “transform,” but “evolve.” They don’t “die”; they simply “faint.” The entire ethos can be succinctly summarized as the glorification of completionism embodied in one long fetch-quest: “gotta catch ‘em all!”

My conceptual analysis of the game looked at the hybridity between this fantastical myth and the augmented reality technology bringing it to life in the real world. This effectively created a superposed layer of meaning “hovering” over the neighbourhood, accessible only by other trainers through the app, as everyday places take on an additional significance understood only within this player community (as PokéStops). It is via their controlled implementation of this “layer of meaning” that Niantic exerts their dominant position.

PROTOTYPES

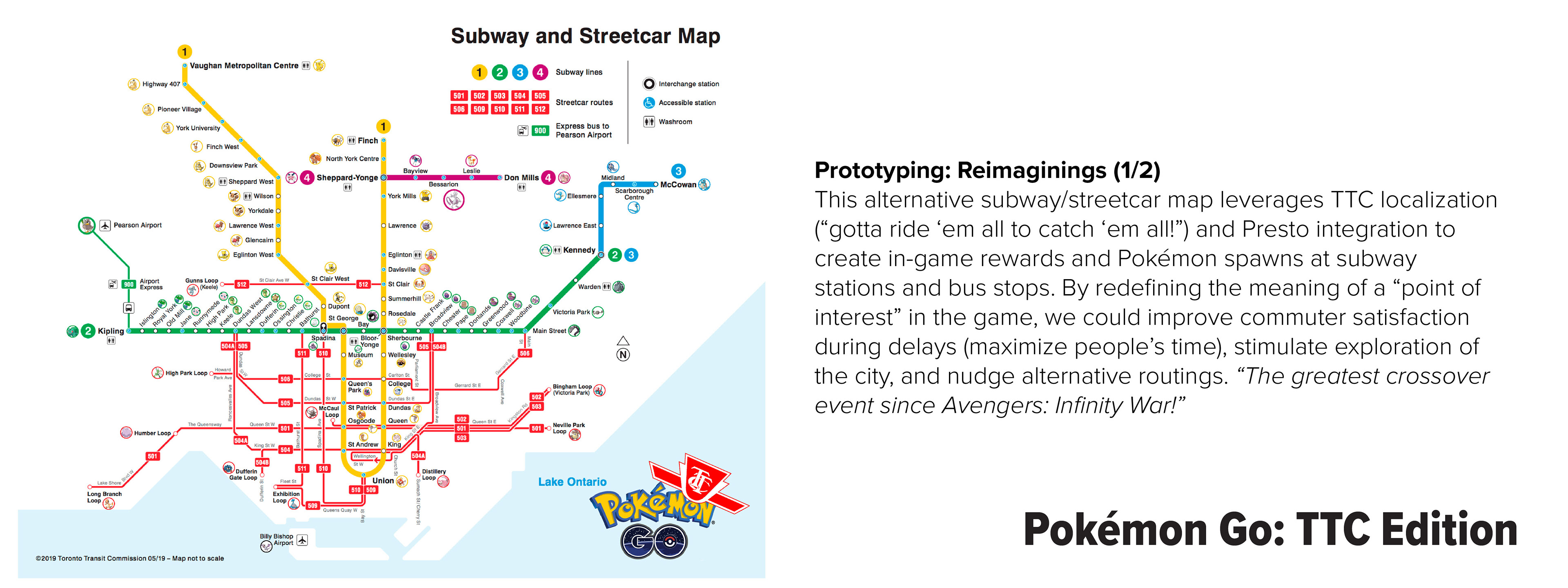

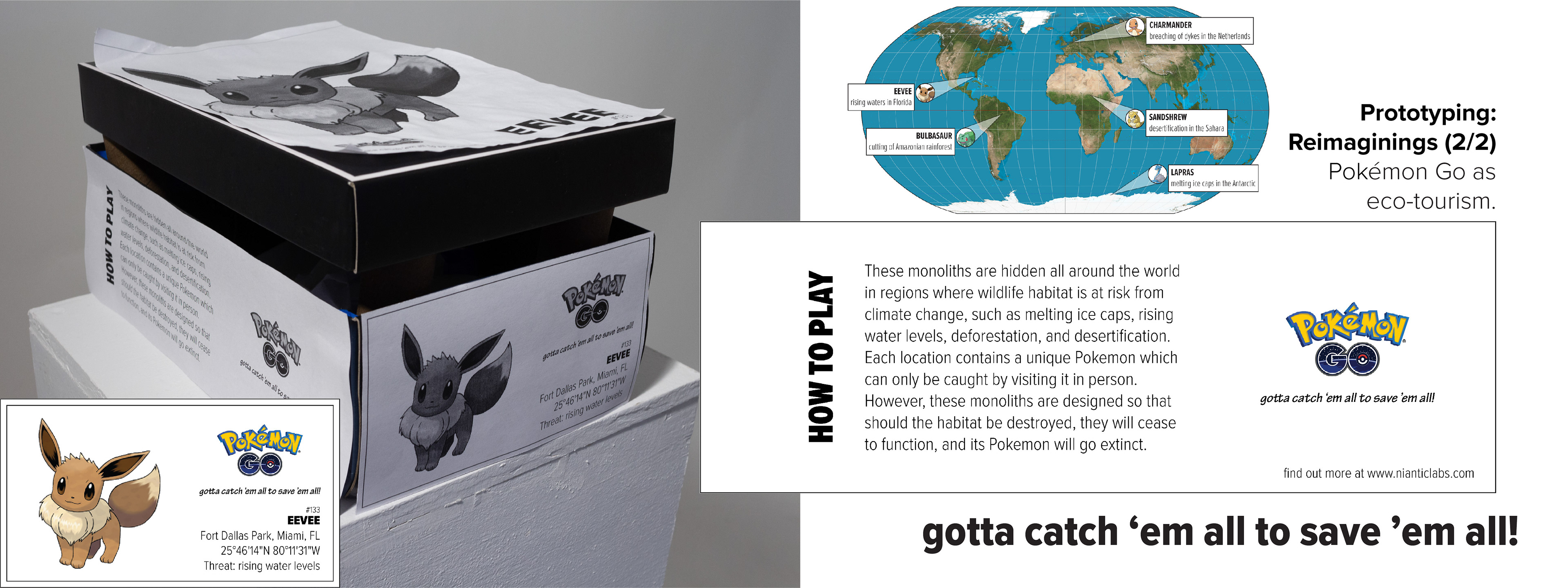

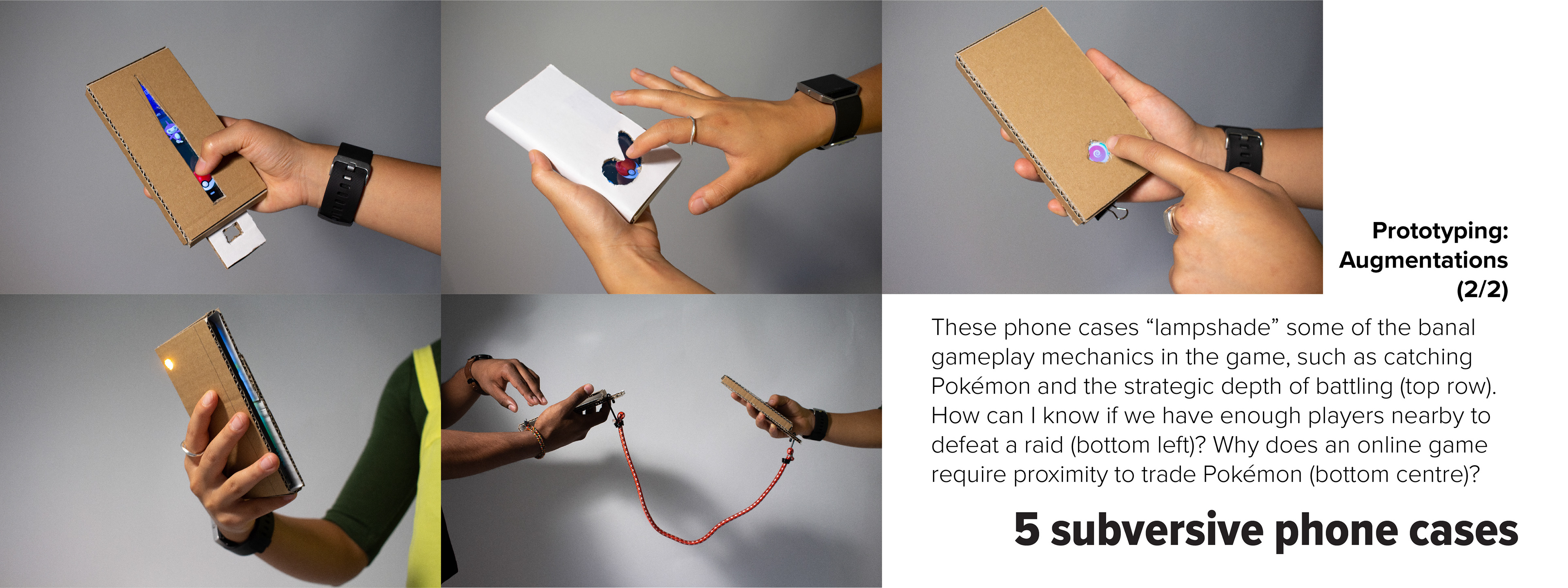

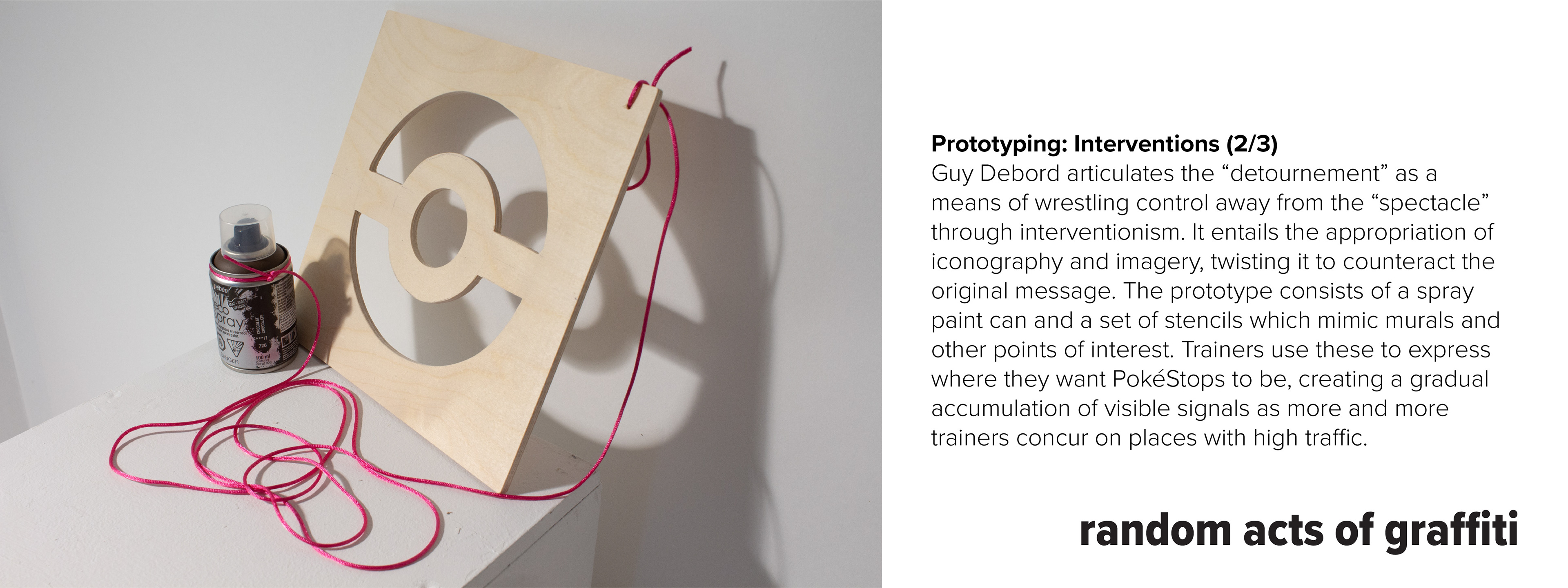

Interspersed with my research, I created several rough prototypes through a speculative/critical lens. They can be split into three phases of exploration: reimaginings, augmentations, and interventions. Some of them show a more light-hearted or satirical bent.