CHALLENGE:

How might Kolding Hospital's emergency department improve patient experiences in its Zone One waiting room, without the budget to hire more staff?

How might Kolding Hospital's emergency department improve patient experiences in its Zone One waiting room, without the budget to hire more staff?

SOLUTIONS:

• A set of communications guidelines for nurses to keep patients informed on waiting time updates

• A more humanizing room layout to de-isolate patients from caregivers

• A waiting room volunteering program to evangelize patient concerns and shore up gaps in non-medical care

METHODS:

• semi-structured interviews

• ethnographic observation

• K-J analysis (clustering)

• empathy mapping

• service blueprinting

• experience mapping

• case studies

• scenario-writing

• semi-structured interviews

• ethnographic observation

• K-J analysis (clustering)

• empathy mapping

• service blueprinting

• experience mapping

• case studies

• scenario-writing

MY ROLES:

• research planning/synthesis

• strategy, ideation

• presentation diagrams

• volunteering program report (final deliverable)

• research planning/synthesis

• strategy, ideation

• presentation diagrams

• volunteering program report (final deliverable)

DURATION: eight weeks full-time

PROCESS FLOWCHART

DETAILED PROCESS

PROJECT FRAMING

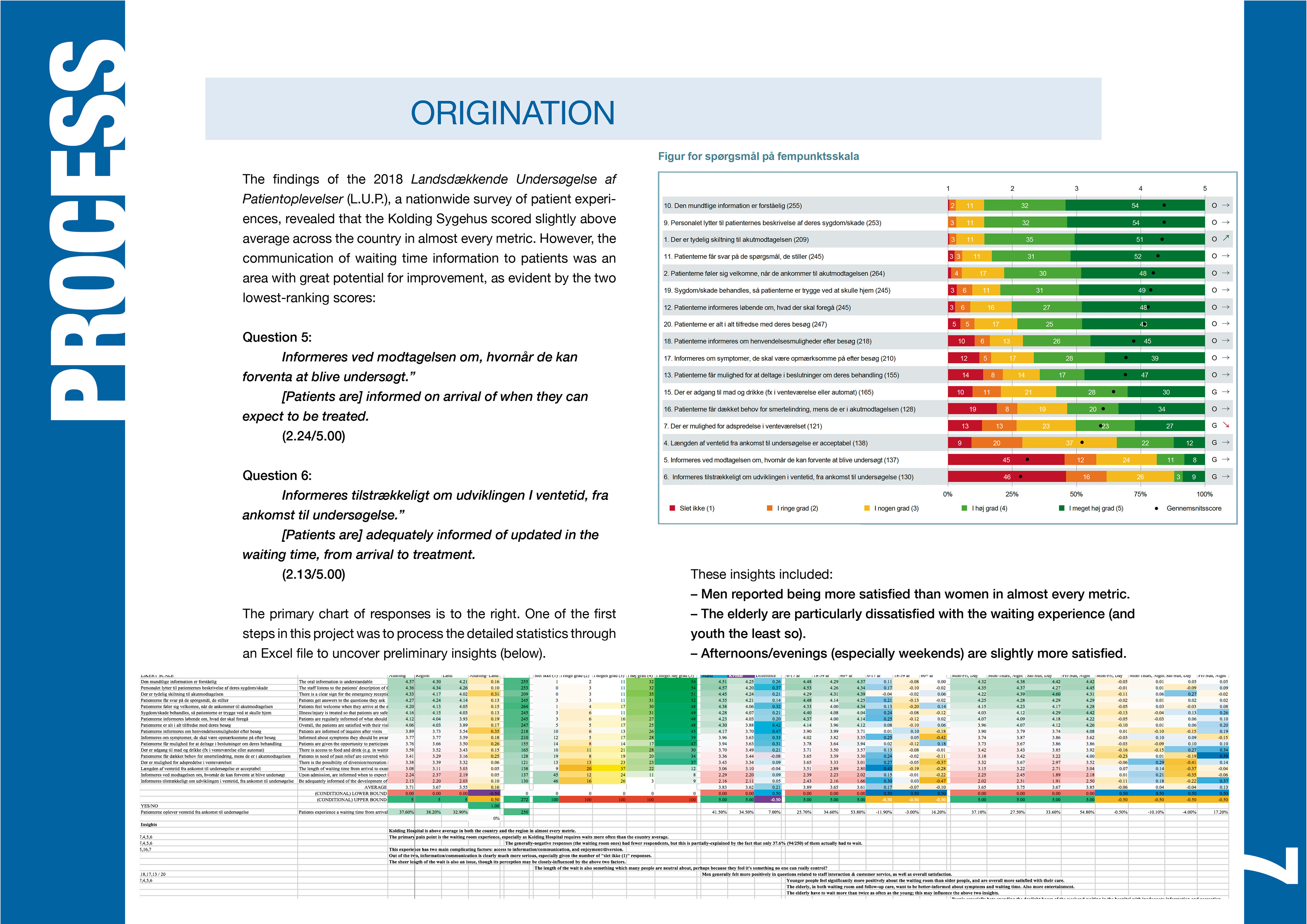

Every year in Denmark, the government conducts Den Landsdækkende Undersøgelse af Patientoplevelser (The National Survey of Patient Experiences). Although Kolding Sygehus scored above-average in most metrics, one area with significant room for improvement was the waiting room experience.

When our class walked into the briefing room on the first day, this was the challenge laid out to us by the head doctor of the emergency department.

PRIMARY RESEARCH

To get a better handle on the situation, our group performed ethnography and spoke with patients, staff, and administrators. Though the vast majority of Danes spoke English, we conducted our interviews in Danish to build rapport with our participants and encourage them to express themselves more fluently. (I relied on my group members to translate after the fact.)

Compared to my strict “by-the-books” training in design research at OCAD, where nothing took precedence over ethics and methodology, here at DSKD, the approach was laissez-faire; put simply, the professors encouraged us to just “go out there and talk to the people.” As a group, we opted for a middle-of-the-road approach. Before initiating our research, we spent some time hashing out what questions we wanted answers for, how we would obtain them, and from whom.

ANALYSIS

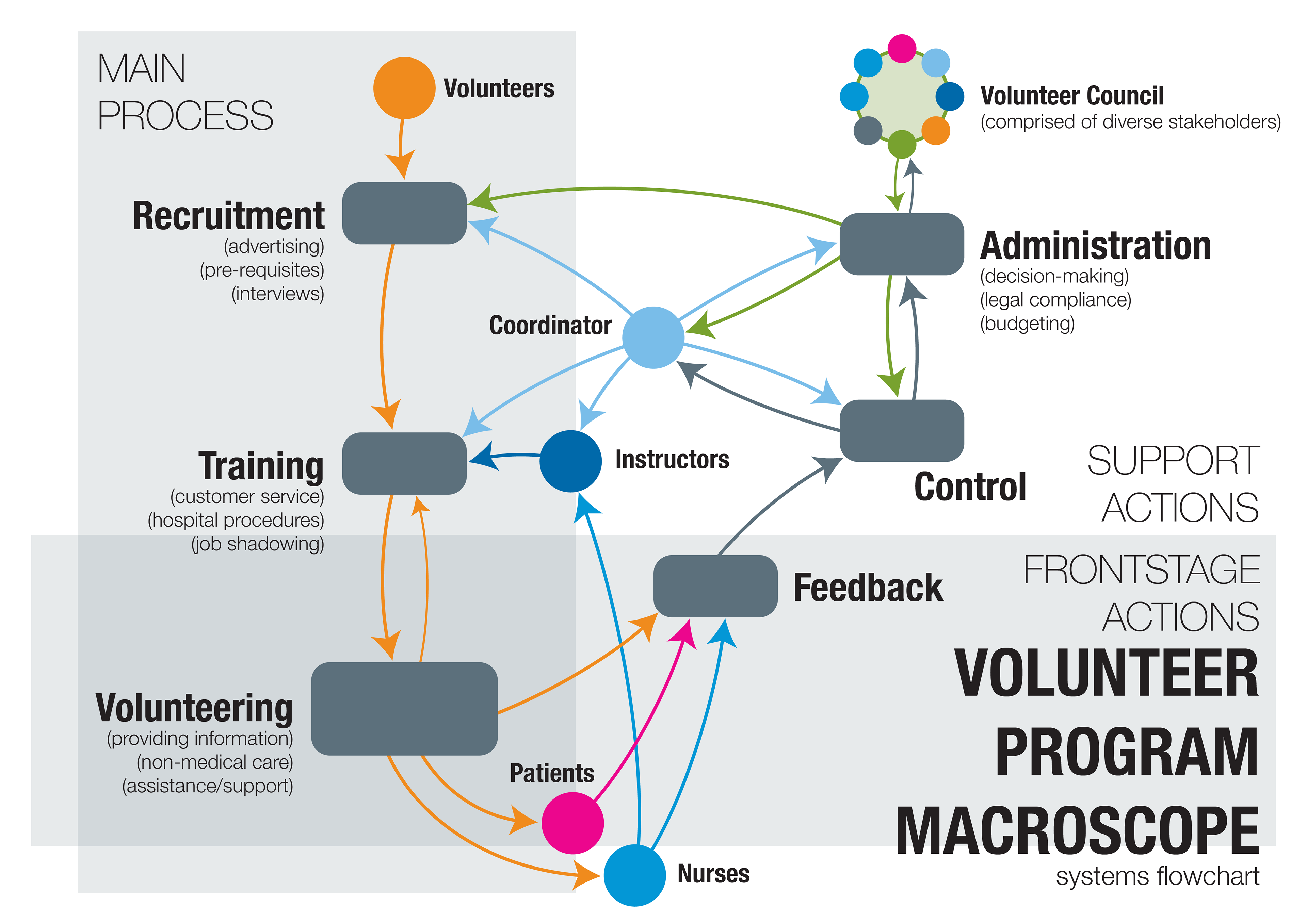

We filtered our research through a gauntlet of service, experience, and systems lenses. Two key methods we used were K-J analysis (i.e. sticky-note clustering) and service blueprinting. After consolidating the interview data and our individual observations into one big picture, we were able to hold a productive conversation about the nuances embedded within our findings.

Thinking extrinsically with sticky-notes and other tangible supplies enabled us to pattern our signals into groupings and outliers as a team. The advantage of this method was that everyone had the power to contribute and understand what was going on, because we were literally working on the same page. (Five hundred sticky-notes were harmed in the making of this project.)

It was also an eye-opening moment for me, learning about the cultural specificities of living in Denmark from my own group members as they interpreted the participants’ responses while sharing their own experiences.

FINDINGS

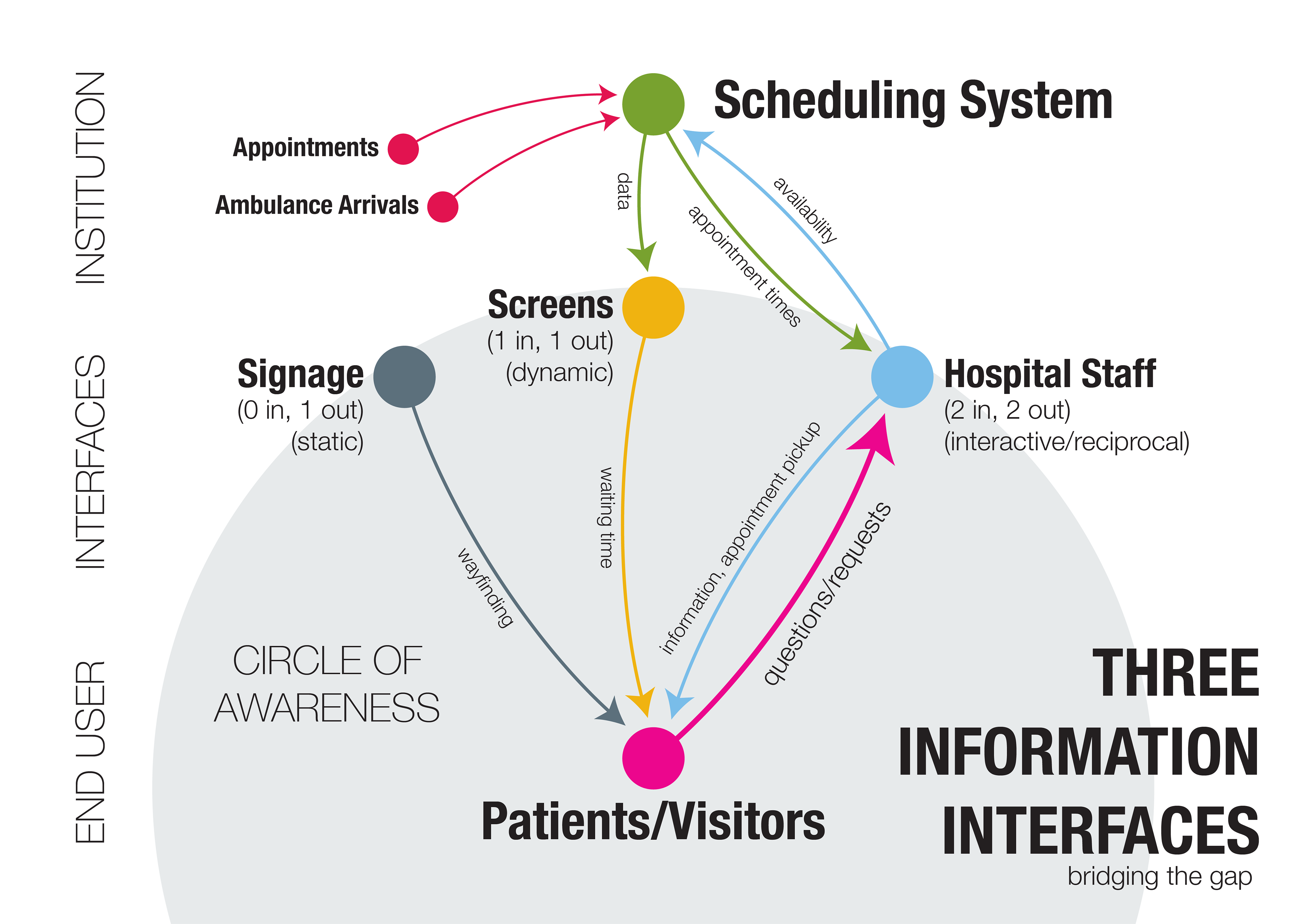

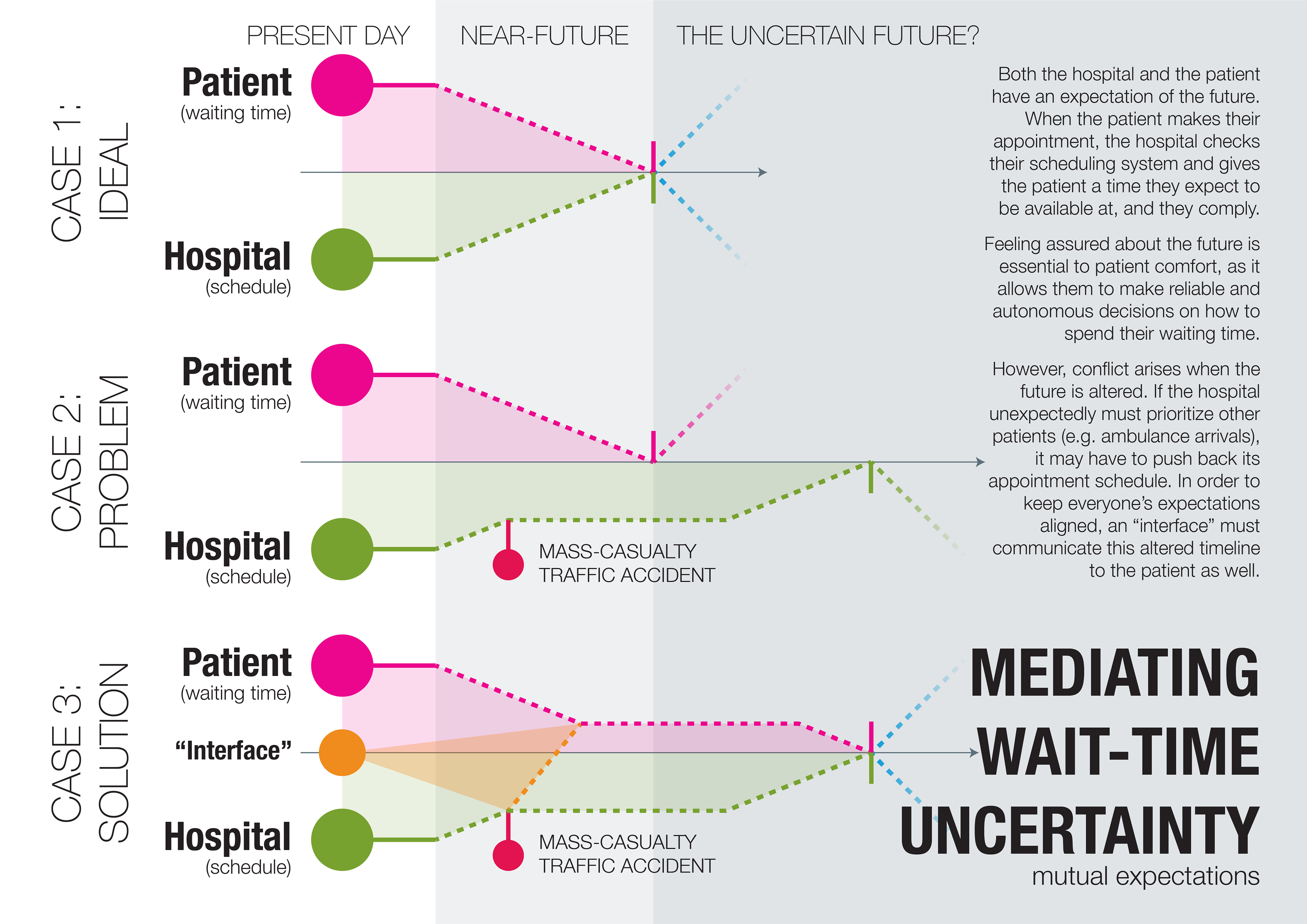

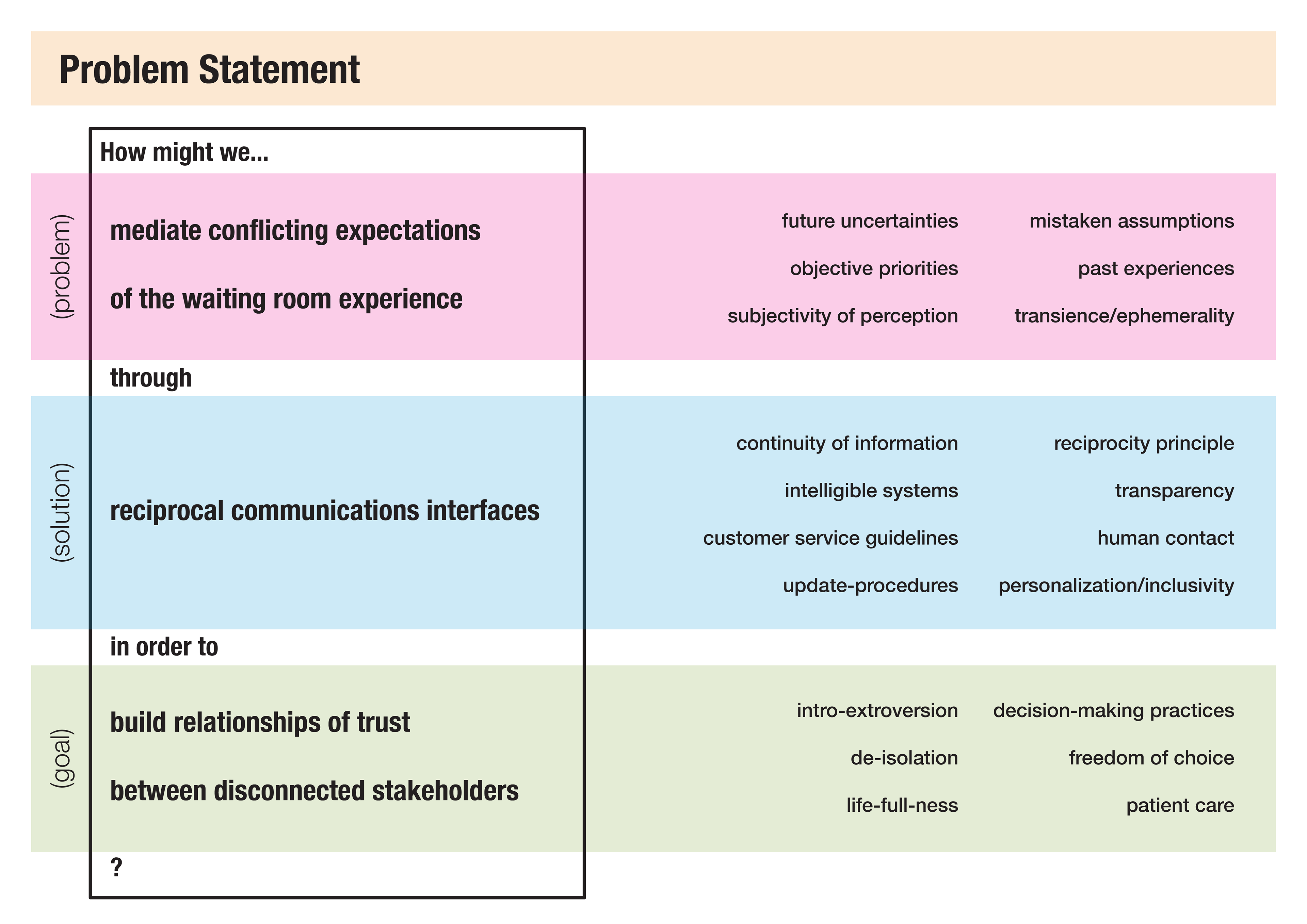

The core theme we found was a lack of communication. While a plethora of systems converged upon the patients in the waiting room, very little feedback found its way back out. Initially, we focused on the waiting time information, which was consistently and deliberately vague. Nurses often did not inform patients of delays. Patients were stuck contending with a confusing screen system featuring colour-coded names bouncing around like an old screensaver; nurses explained it reluctantly, or not at all.

Environmental and systemic factors exacerbated these tensions. The reception desk was not in the waiting room’s line-of-sight, contributing to a perceived lack of care through isolation. And in fact, the hospital administrators had already added such coveted implements as a coffee-maker, a vending machine, and a (partially walled-off) children’s play area—to little effect. After all, patients and nursing staff were not consulted on them.

SOLUTION

We settled on three ideations: a communications procedure for nurses, a new waiting room layout, and a volunteering program. Out of the three, I took charge of the latter.

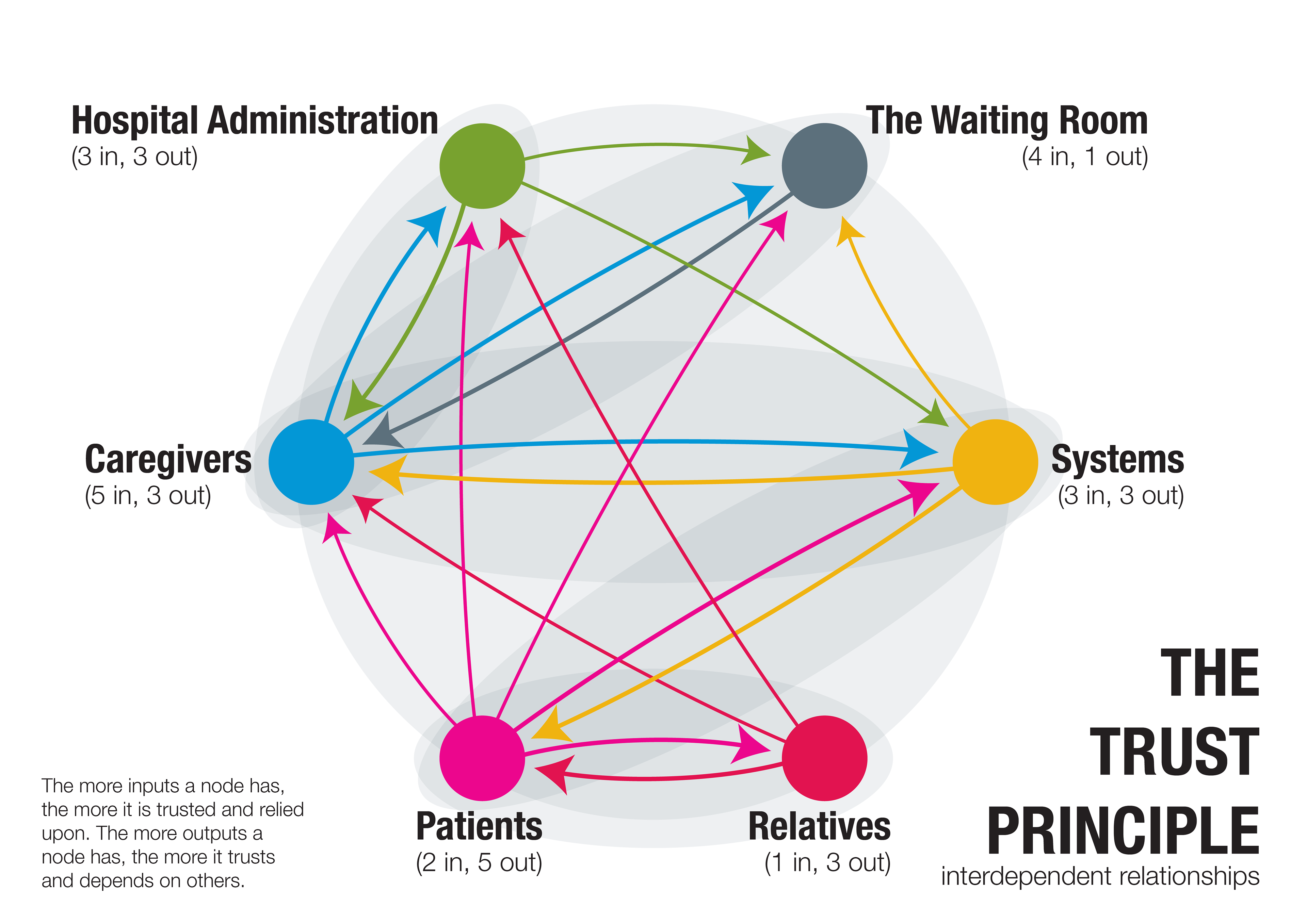

The volunteering program revolved around a principle of reciprocity, where every interaction between patients, staff, volunteers, and the hospital institution contained an exchange of mutual benefit. In the report, I outlined its implementation, including its mission, administrative structure, recruitment process, and visual identity. To support the feasibility of this proposal, I cited case studies and precedence from other hospitals in Denmark and internationally, as well as our primary research.

We handed the printed booklet to the head doctor during our final presentation at the end of February. Last I heard in June 2019, the hospital has “already [had] some thoughts on using volunteers on basis of this well-written document.”

FINAL REPORT