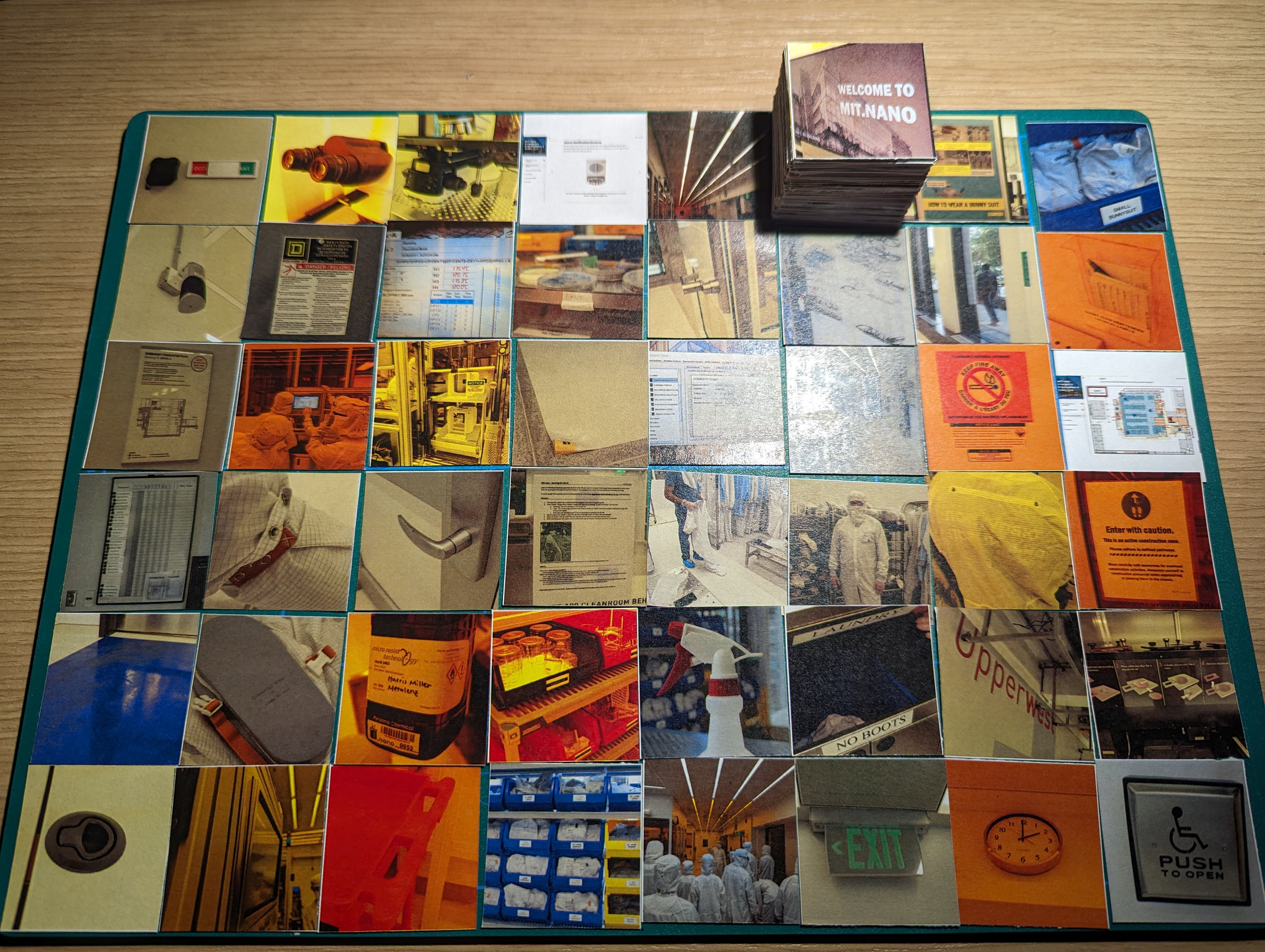

BEFORE human interaction

AFTER human interaction

A clean room is a home for scientific instruments. For the sake of technology, it is designed to remain as sterile as possible, with sensors, ventilation, personal protective equipment, and other systems working in concert to prevent humans (or anything else from nature) from leaving any trace of themselves.

Yet at the same time, the clean room is inseparable from humans. The clean room needs people to maintain it, clean it, and fix it. The machines don’t run themselves. Students and faculty have input into committee decisions that drive what tools are installed. Then humans install them.

In search of human traces in this paradoxical environment, I applied two user research methodologies from my human-centred design practice—namely, ethnographic observation and semi-structured interviews. I interviewed clean room users about their clean room experiences. I underwent the clean room training myself, to experience what it took to get access to it. I went into the clean room with a camera and took photos of every human trace I saw.

Curating user insights is a constructivist process of patterning not unlike the natural sciences, of eking coherence out of chaos, of piecing together theories about causation from little pieces of experimental evidence, of looking for moments of entropy and contradiction where an established order starts to break down.

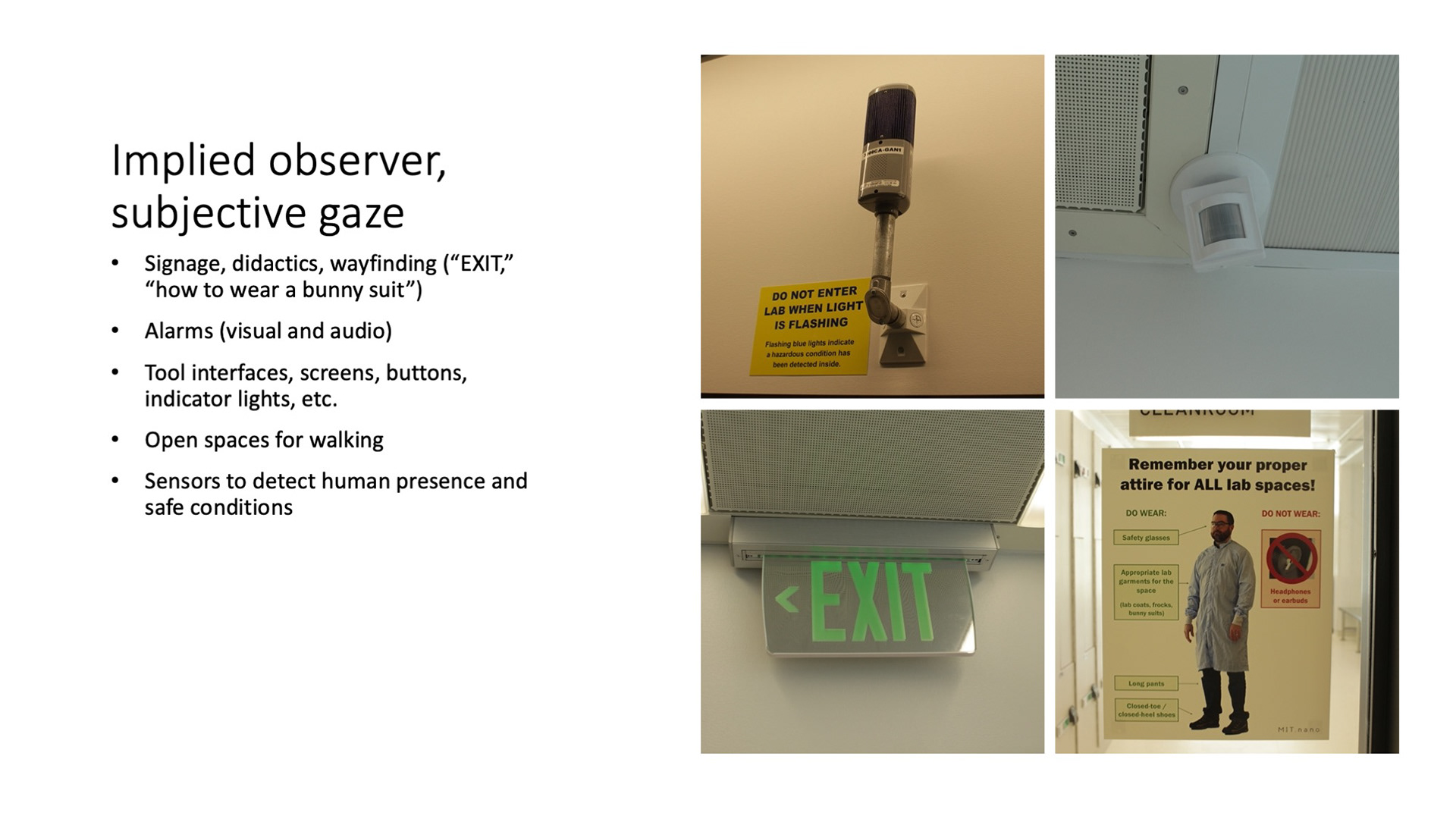

Sometimes, human traces are disembodied and accumulate over time, belonging to nobody, like wear and tear. Other times, the trace is a specific expression of self-identity or ownership—a written name, for instance—in an otherwise communal environment. And moving beyond the tangible, there are traces that can only be inferred: a sign (permanent or ad hoc) expects somebody to read it, a motion sensor is aimed to detect a mover, a system (of scheduling, of organizing, of language) needs a culture to create it, a mess can be made or tidied up, and so forth. Seen or unseen, the human agents who leave these traces have a way of making themselves visible. There is an intelligent design behind such things.

In earlier iterations, I experimented with both my own judgement and with ChatGPT to categorize my photos into typologies and sort them into grids along various axes. But rather than control the final output myself, I left it up to passers-by, who are invited to iterate on the art—a communal mode of organization which parallels MIT.nano: a shared space belonging to no user in particular. A sterile whiteboard mounted on a wall holds fridge magnets with glossy photos and dry-erase markers. The result is responsibility disembodied, as people can rearrange, annotate, add, or steal images as they desire. I supplement this evolving art-organism with edited interview transcripts and other documentation of my research.

As a non-impartial researcher, I am pushing my own agenda here: to celebrate the diversity and nuances of human subjects that persist in spite of an environment that doesn’t really seem to want them there. After all, what is science without the scientist?